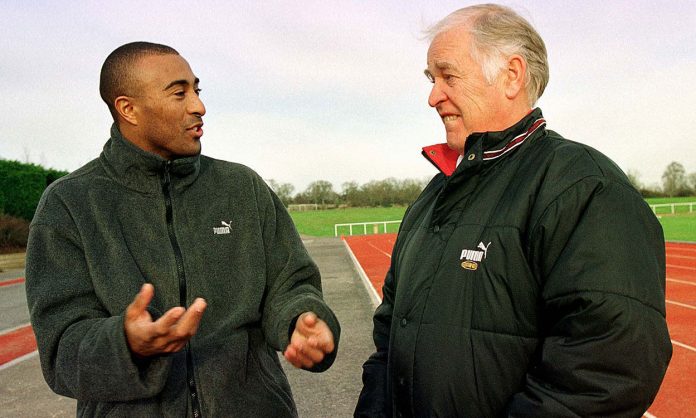

Former Great Britain Athletics head coach and hurdles guru chat George Mallett about a life in athletics that is impossible to replicate in the 21st century.

For more than 55 years, former nationally ranked triple jumper Malcolm Arnold coached some of the best hurdlers the world has ever seen, from helping John Aki-Bua win Uganda’s first ever Olympic gold in 1972 to the world-winning exploits of Colin Jackson, Mark Green McCoy and Day. During his varied career he has also been Director of Coaching and Development as well as Head Coach at UK Athletics.

As a young coach, in the late 1960s you landed the position of Uganda’s national coach. How did that work out?

I was a pedagogic teacher. I went to Marple Hall School (in Cheshire) for three years and then went to Bristol for three-and-a-half years as head of department at a school that had its own track, so I had to organize athletics all the way up to county level.

The Uganda National Coach position has been advertised in Athletics Weekly. At the time I was still competing myself somewhat and working with Dave Kay, who was the national coach in the South West.

As well as coaching myself, Dave coached other athletes and oddly he coached the then British number one 400m hurdler Colin O’Neill. I listened to Dave. This was my education.

I applied for the job, went down to the Ugandan embassy in Trafalgar Square and had an interview with the chief executive of the Uganda Sports Council, who went to Loughborough University like me, and another guy called Agray Awori, who was a very good sprinter. I think the only other person they interviewed was an old man who was a sports officer in colonial Uganda.

Were there any key athletes you were aware of at the time?

My first Olympic final: Amos Omolo, 400m runner. Amos was four years older than me. He was 32 years old, I was 28, and when I started helping him, I was immediately warned against the powers that be in the sports council. (I was told) “It is lazy, it is wasteful, it is useless” and so on.

That’s not what I saw, so I ignored what they said, continued to train him, and saw that he was quite talented. He had a good history behind him, but then he was poor two or three years before I came.

I learned so much from that guy. I don’t know where he got his workout ideas from. I was basically a jumps coach when I went there. I knew quite a bit about running, but not internationally. That boy taught me a lot. It put me in good stead with John Aki-Bua.

We selected Amos for the 1968 Olympics in Mexico. They didn’t really want him in the team but I insisted and he made it to the final and scored an African record of 45.3. He ran an African record in the first and second rounds, then he bowled it in the final as he was in the eighth lane with Lee Evans inside him, who won it in 43.83, a world record that has stood for centuries.

Amos ran like he was shot from a 300m gun and died in the last 100m so that was another big lesson for me in 400m tactics. I got hold of the race footage and could extrapolate from that what the split times were. Amos went through the 200 in 20.8 I think, while Evans filled in 21.2 and ate him alive in the home straight.

Being of such an age you should be almost friends?

I like to think that every athlete I’ve coached, or almost every athlete I’ve coached, we’ve been friends. That’s the important part of it all. Some athletes I still have relationships with nowadays. Many coaches overcome this with an authoritarian approach.

When you first start with an athlete, it tends to be authoritarian; “do this, do that. That’s your training schedule, go ahead.”

But I always told the athletes. “As you get older and improve and experience better, you get to the stage where you know more than I do because I’ve told you everything I know and you’ve gone there and done it.”

If the athlete filters out ideas from his own experience and the coach is the type who doesn’t like to be questioned, it spells disaster. If you are an authoritarian with an international who has been there and done that and probably knows more than you do, and you still insist on pontificating, that’s where the relationship explodes.

You famously formed a relationship with John Aki-Bua, culminating in his world record breaking 400m hurdles at the Munich Olympics. What memories do you have of that day, I heard he had a pretty unusual race day.

I remember athletes getting paid by shoe companies, but in those days everything was a brown envelope. In these, John was paid by Puma, looked after by (former world mile record holder) Derek Ibbotson. I knew him very well and Derek knew about the fact that Adidas had tried to rip John off by promising to pay him off and do something dirty to Puma.

You can always tell if it’s the first round or the semi-finals (of those games) by John’s boots. Puma in the first round, Adidas in the semi-finals. Of course, Puma skimped because they had already paid him money and had to pay him before the final.

Derek came to me and said. “Here, put this in your pocket and I want you to promise you’ll give it back to me if he wears Adidas or you can give it to John if he wears Puma.” John was going to wear Puma for the final, he had to talk, but the Adidas people had already put some coins in his way. And Adidas was coming along too. Two Adidas guys followed John around his warm-up.

He came out wearing Adidas shoes, but he had a Puma in his bag and he wore a Puma, so I handed over $5,000 to John in a brown envelope. That’s about $50,000 these days, and that’s what I remember about the finale. Whether it was good that they were chasing him, which took his mind off the bad stuff, I don’t know.

John was notorious for his work ethic at the time. Have you ever trained anyone like this?

all of them. Any athlete who succeeds has an incredible work ethic. In fact, for Dai Green, his work ethic was his downfall because he didn’t know when to stop.

He lived with his girlfriend Sian near us in Bath. He was training with me in the morning and it wasn’t going to be easy and then Sian told me eventually that he would go out and do more stuff in the afternoon. I couldn’t figure out why she was absolutely devastated the next morning. He didn’t know where to stop, and he couldn’t be told.

Dye was one of four world or Olympic champions you coached alongside Mark McCoy, Colin Jackson and the aforementioned Aki-Bua. Are there non-medal stars who have created different types of heights?

Lawrence Clarke was absolutely brilliant. Sir Lawrence now (Sir Charles Lawrence Somerset Clarke is more correct)! Lawrence was an old Etonian who had come to Bristol Uni, and he was a decent English school sportsman, but nothing special. His mother, who is the dominant force in his life, said: “We need to find him a coach.” He brought him by ear to the University of Bath and said: “Here’s my boy, I’d like you to train him.”

Therefore I said: “I will consider it. Let him do a few training sessions with us first and then I’ll decide because it’s not fair on me, you’re giving me someone who doesn’t accept coaching and so on.”

There’s nothing worse than a dead duck in a good training group, so he goes and warms up and does this and that and the other, and after about a minute I said to his mom, “He can stay.” He had the kind of quick limb movement that is an absolute must for a sprint hurdler, and at the end of the day his big problem was that he wasn’t as quick on the ground as Jackson or McCoy were.

At the 2012 Olympic final, I was sitting with his mother, Lady Clarke, and two sisters, right at the start of the race. They insisted that I come and sit with them in this incredibly expensive seat that they bought, and I got to see the race from the back. I said: “Bloody hell, he’s fourth!”

It was a really incredible moment because he wasn’t supposed to finish fourth in the Olympics, but he did. He was nowhere near a bronze medal, but it was incredible for him to do what he did, achieve what he achieved, European Junior Champion and so on. Really brilliant.