Trevor Ariza first noticed his son was different in a fourth-grade basketball game. After breaking the poor 8-year-old with one step, Taj Ariza drove into the paint and threw a seamless pass from behind to the open shooter. “The timing was perfect. It was rare. It was just a perfect pass,” says Trevor.

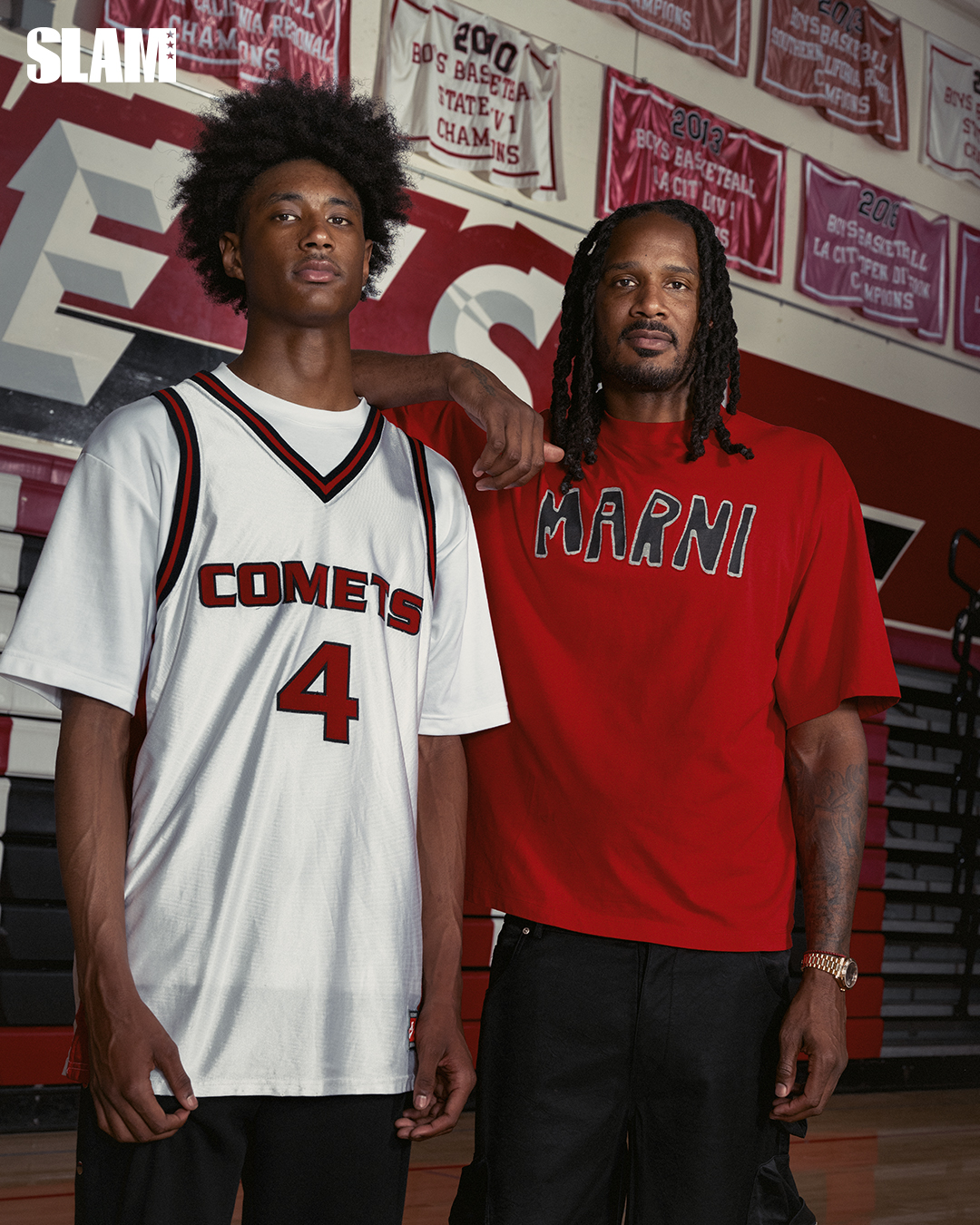

It’s a typical sunny day on the west side of Los Angeles, and Trevor, Taj and Tristan Ariza are trying to see who can hit the first half-court shot. It’s been two years since the NBA champion and Los Angeles native retired, and today he returned to the campus where his basketball dominance began. Except Trevor isn’t himself in his old white, red and black threads. His eldest son, Taj, is

Taj is currently one of the top 16-year-olds in the country, and next fall he’ll make his mark on the same court his father did. After finishing the basketball season at St. Bernard HS, Taj soon transferred to Westchester this spring.

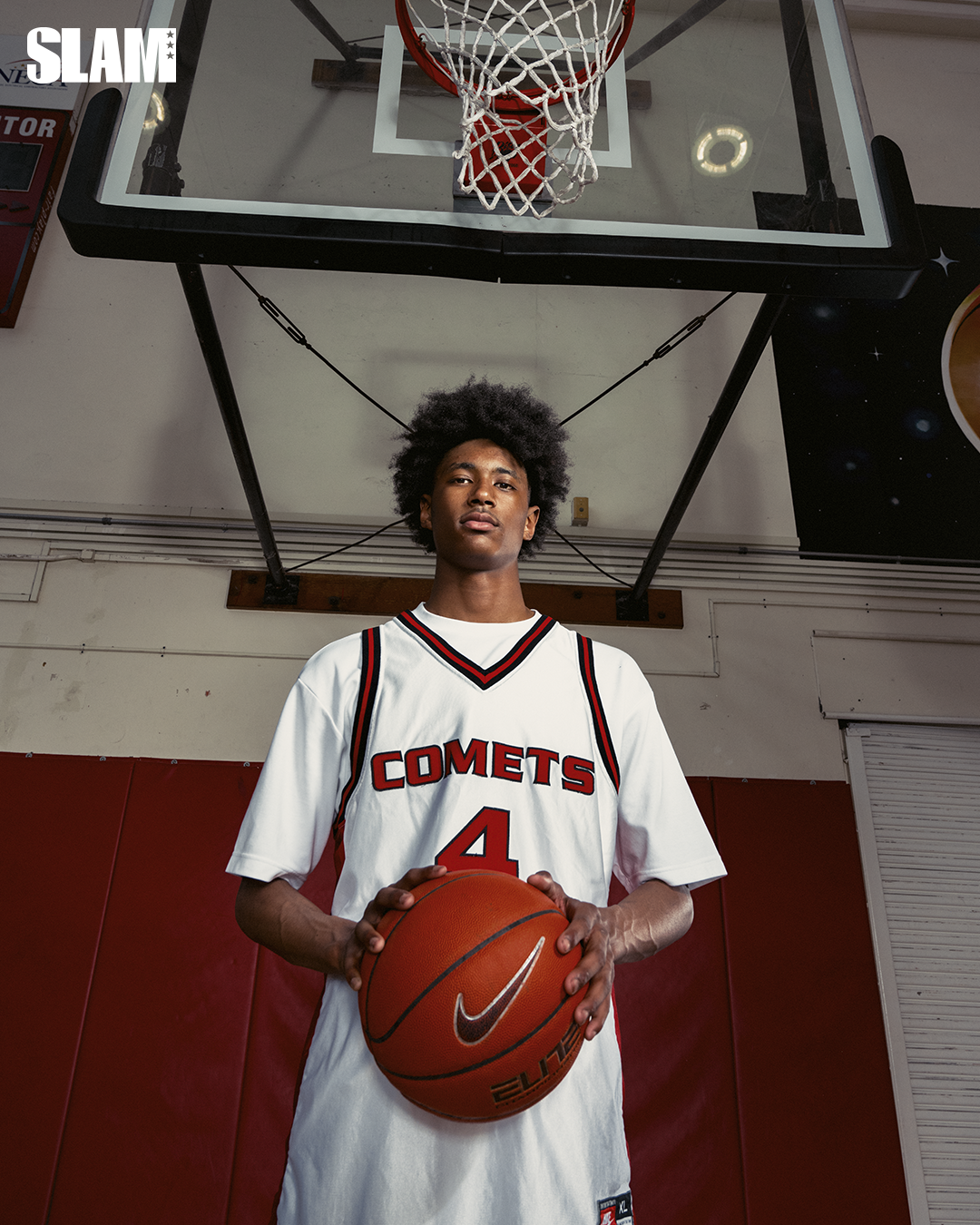

In the school gym, Taj stands at half court, surrounded by a sea of red, black and white, from the Comets-branded bleachers and walls to the shades of his dad’s original No. 4 home jersey, which he wears. Faded banners displaying Trevor’s two state titles with the Comets hang proudly as father and son pose for movies. Even now, Trevor’s influence is ever-present. It’s surrounded Taj since he was a kid, hanging out with Kobe and Derek Fisher. Yes, he is the son of an NBA player. But Taj Ariza’s game is all his own.

“I have to keep working every day,” says Taj. “You know, my dad (had) a great career, but I want to have my name and show people like: oh i want to be like her you know. So I just have to keep working so I can get there.”

The rising 6-8 junior exploded in the recruiting circuit and is now considered a top-10 prospect in the 2026 class. He held just three major DI offers after his freshman year. Last year, he racked up five more in five months. Last spring, he was invited to the US Junior National Mini Camp, and this summer he played with Team Why Not 17U on the EYBL circuit. Things are just clicking.

But the path was not so easy to chart. Trevor allowed Taj to find his love for the game. He didn’t push, he didn’t push; he sat back and watched his son discover their now shared passion.

“My idea of him was always right before he got to high school, if he was serious about it, I would give him all the tools that I use or the things that I learned to help him. So I would say when he got serious about wanting to get better or actually want to work in basketball was in ninth grade,” Trevor says.

Taj agrees. He loved the game, but there’s a big difference between loving the game and loving something enough to put you through 5 a.m. practices, twice a day and a grueling 82-game season.

“I had to change my habits. I didn’t really take it that seriously until maybe high school. I guess it was just fun for me. Sure, it’s still fun, Taj says, but now I see that I have a real chance to do what I want to do and be great. And I just kept going. I just picked it up.

Just before Taj entered his freshman year, Trevor laid out what his highest potential would look like for his son. It ended with a gentle but gentle reminder. Time to kick it into the next gear. “I sat down with him and told him it’s not going to be fun. Most of the time, it won’t be easy. A lot of sacrifices will be required. And most kids, when they hear about sacrifices or taking away fun or free time, they kind of avoid things. Lucky for me, he wanted to do it. So it was easy,” says Trevor.

Within a year, Taj and Trevor developed a dedicated program. At least three times a week before school, they either lift or grind in the sand with Trevor’s old Hoop Masters teammate. Working on the soft sand of Los Angeles beaches is taxing, tiring, stressful—all of the above. But his explosiveness has increased. “I started choking on people, so that’s when I noticed it started to help,” Taj says. Off the court, he studies the ways bigger guards like Paul George and Brandon Miller have created space off the bounce.

After a shower, breakfast, and school, Taj will sound off with whatever program they didn’t do in the morning before hitting the court for a myriad of shooting and ball drills. From the gym to the dunes, Trevor is right there with his son.

Taj’s dedication is stubborn, a combination of witnessing the professional streak of his father’s career and a will to destroy his own legacy. Waking up at 5:30 a.m. to run on ever-shifting sand is as much a mental workout as it is a physical one. While Taj accepts the results of his work, Trevor sees it as a mile marker of how far his son has come since the freshman talk.

“It’s easy for him, especially being so young, to get caught up in the attention that he gets and kind of get complacent and stuck in it. And my message to him is always to just put your head down and focus on the work that you’re putting in,” says Trevor. “Focus on the hours you spend in the gym, in the sand, watching the game, learning the game, just focus on that. Everything else will take care of itself.”

When he moved from North Carolina to Los Angeles to attend Saint Bernard HS as a sophomore, Taj says the talk surrounding his game remained relatively quiet, aside from the allure of his last name. That was before the start of the season, when he received his first two offers from the University of Washington and USC. He still has the reaction video on his phone. “I was so excited. I was jumping up and down, shouting. It felt good to finally get, you know, what I felt I deserved. But it also just motivated me to keep going. Just keep piling on it,” Taj says.

To witness that joy in one’s relatives is a pride only for a parent. Trevor, meanwhile, started cutting his tips even after an 18-year career at L that featured a 2009 championship with the Lakers and stops at 10 different organizations. The guidance he gives his sons is often rooted in the steps he took on his NBA journey. And just as their games are different, so are the options and decisions available to them.

As Taj prepares to enter his junior season and his younger brother Tristan also starts school, Trevor knows he can’t juggle the roles of coach, dad and teacher all at once. He must be selective and careful about the hats he wears and when he wears them.

“If there’s a week where I’m overwhelmed, e.g. Clean your room or Take out the trash. How many times do I have to tell you to take out the trash? I have to take it easy on what’s going on on the court because at home I’m taking it hard on them,” Trevor says.

If Tajh takes care of business at home, Trevor will leave more knowledge behind. “But then again, it’s his canvas. So he has to paint it as he sees it. I can only fix little things or give him little bits and pieces until he comes to me for the big things.”

Big things like transferring to your dad’s alma mater.

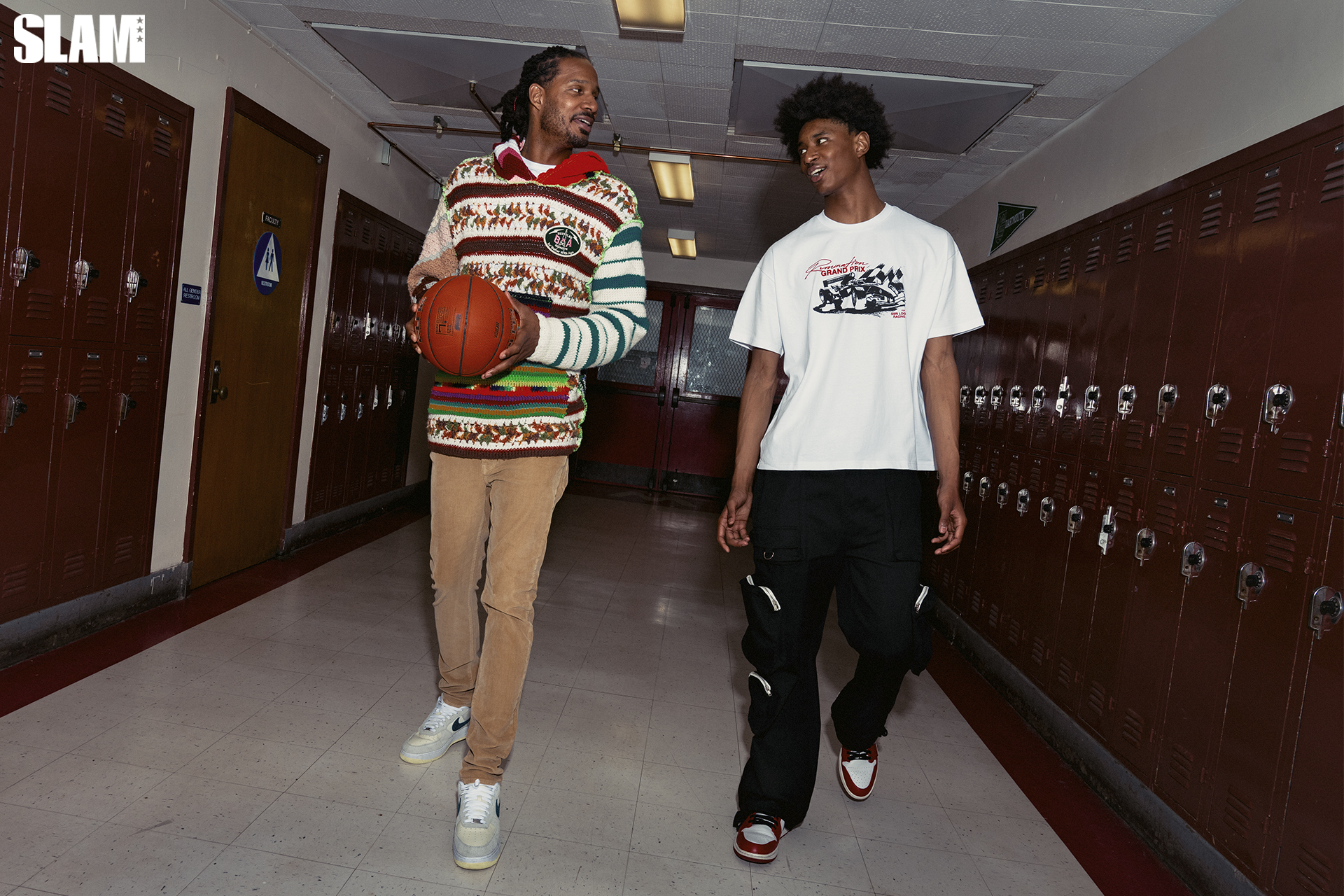

As he looks at the posters his father put up decades ago, Taj feels the target on his back expand. His teachers are already regaling him with memories of the school’s legendary past battles with cross-county rival Fairfax. But noise is just that, noise. And as his father walks the halls he once occupied, he knows that Taj is ready to fully enter his hall.

“I think for Taj, he’s always been around it. So it’s almost like second nature,” says Trevor. “He’s been around since he could walk, since he could talk. It’s tailored for him. Some children are born to do certain things. And for me, in my eyes, I feel like he’s one of those kids that was just born to be in this space.”

Portraits by Sam Mueller.