The sheer shock that comes with a putt is more than enough of a distraction from the truth. We are so immediately and regretfully forced to accept bogey while feeling as if we deserved it, that most of us have never bothered to ask a natural follow-up question:

What the hell just happened?

As it turns out, lip protrusions offer a great lesson in mystifying physics, as evidenced by a recent study called “Mechanics of the Golf Outboard,” published this week in Royal Society Open Science.

Authors John Hogan and Mate Antali know a lot more about math and physics than anyone who owns one Scotty Cameronbut their latest work analyzed the forces at play when a putt approaches the edge of the hole, touches the rim and, at times, seems to defy gravity.

In the most basic sense, your shot is simply acting on various forces such as speed and angular motion that determine results based on where the ball enters the hole. Hogan and Antali divided the area of the golf hole into sections and found that the expected actions of a golf ball on the absolute rim of the hole and the area below the rim create two distinct types of lip protrusions:

– edge to edge outside

– Lip hole outside

Rim outs are much more common, as hole outs are expected to occur only when the ball’s center of gravity (its center) drops below ground level – or begins to disappear into the pitcher. They happen, of course, not so often, as we will venture to explain below.

;)

Courtesy Royal Society Open Science

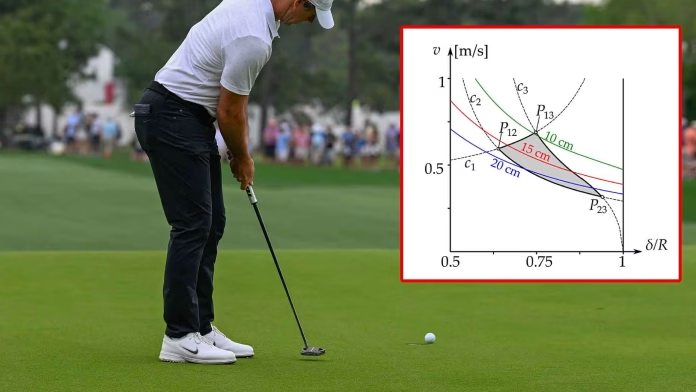

The angle of their study that seems easiest to understand came in the form of these two graphs above. On the left are colored curves showing velocity (y-axis) versus position relative to the edge of the cup (x-axis). Anything above the blue curve is moving fast enough that the ball would lose contact with the edge of the hole and drop in. Anything below the blue curve maintains lip contact – if ever so briefly – and would be susceptible to lip protrusions.

On the right is a clearer view for those who did not take advanced calculus. You’ve numbered regions 1, 2, 3, and 4. Shots involving conditions in region 2 are expected to land in the cup — they likely won’t travel as fast and/or enter the hole closer to the center of the cup (rather than the edge). But region 3 – higher speed, closer to the edge – would expect a “lip edge out”.

The authors achieve these results with no-spinning motion, which may make sense since most shots spin end-to-end near the hole. The study evokes esoteric terms like separation, potential energy, dry friction, and more, which may not mean much to you, but it’s what brings us to the trickiest part of that chart: region 4.

Without spin, region 4 would almost always result in balls falling into the cup – mainly because a standard cup is approximately 10 centimeters deep – but because spin can occur when a ball reaches the rim of the cup it begins to spin AND starts to drop in, shots that move with specific conditions can see the ball dip below the ground horizon and use that spin to find a zero-pitch condition (downswing, in this case), causing them to spin around the jar and soon pop back out of the hole.

It is in that region 4 that a ball can experience a “pendulum-like” motion, swinging around the wall of the cup. It’s rare, but it’s what Hogan and Antali have called “golf balls of death”: truly a golfer’s worst nightmare. (For better understanding, see this video.) As dramatic as the name may sound, it’s simply a nod to the steady state of motion, implemented similarly to the famous circus act “wall of death,” where motorcyclists rip seemingly perpendicular to the ground, using angular forces to stay upright in an enclosed environment. (Yes, that means you have a new name for the worst lips you’ve ever seen – just make sure you use it right. It won’t happen often!)

Now here’s where it feels important to point out: a golf course doesn’t exist in a vacuum. These patterns are defined through standardized shapes in a PDF, not through the contours and architectures we find outside, with different grass grains, moisture levels and weather conditions. Any number of these things can affect a putter’s willingness to drop into the hole or avoid those responsibilities and roll back. And that’s just from Mother Nature. There is always the inner cutout of the hard plastic cup inside the hole, which is not always perfectly perpendicular to the green.

Alas, whether this study has solved the puzzle or not, there is always one conclusion we can all agree on: the more your shot moves to the center of the cup, the better. Because the edge teaches hard lessons.

To read the entire study, click here.