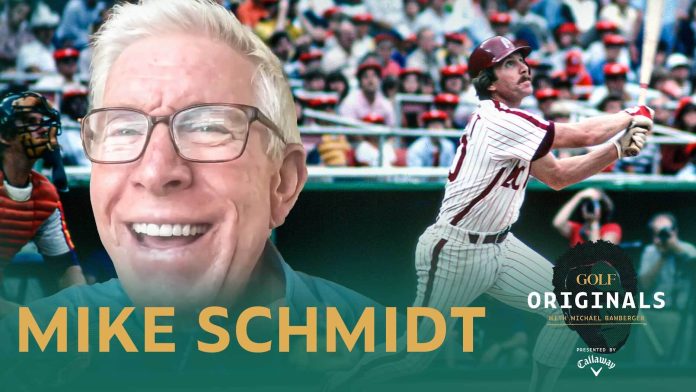

After Hall of Famer Mike Schmidt voluntarily ended his 18-year baseball career in 1989, four months before turning 40, he began thinking about a life in golf. With others, he developed a golf circuit for athletes and celebrities. In his late 40s, he began devoting himself to golf full-time, to see if he could get good enough to make the senior tour. He did very well. But not Bruce Fleisher-Allen Doyle-Bob Duval good.

There are layers and layers, in every sport. Looking back, he says, he spent too much of his practice time hitting full shots into the range, and not enough putting and chipping greens.

“If you keep doing what you’re doing, you’ll keep getting what you’re getting,” says Schmidt on our last page. Original GOLF the episode. He applies this phrase to every aspect of his life.

Schmidt and Tom Watson were both children of the Midwest who were born in September 1949. Schmidt hit 548 home runs without ever attempting to hit a single. He won the Gold Glove as the National League’s third-best defensive player 10 times. He was, overwhelmingly, a first-ballot Hall of Famer. When I suggested, in an hour-long interview that we tried to trim down to 14 minutes, that he would do to baseball what Lee Trevino was to golf, Schmidt said, “I see myself as Tom Watson.”

Fair enough. Joint membership in the class of ’49. Their common childhood (Kansas for Watson, Ohio for Schmidt). Their stoic demeanors. Also, their impatience with false modesty.

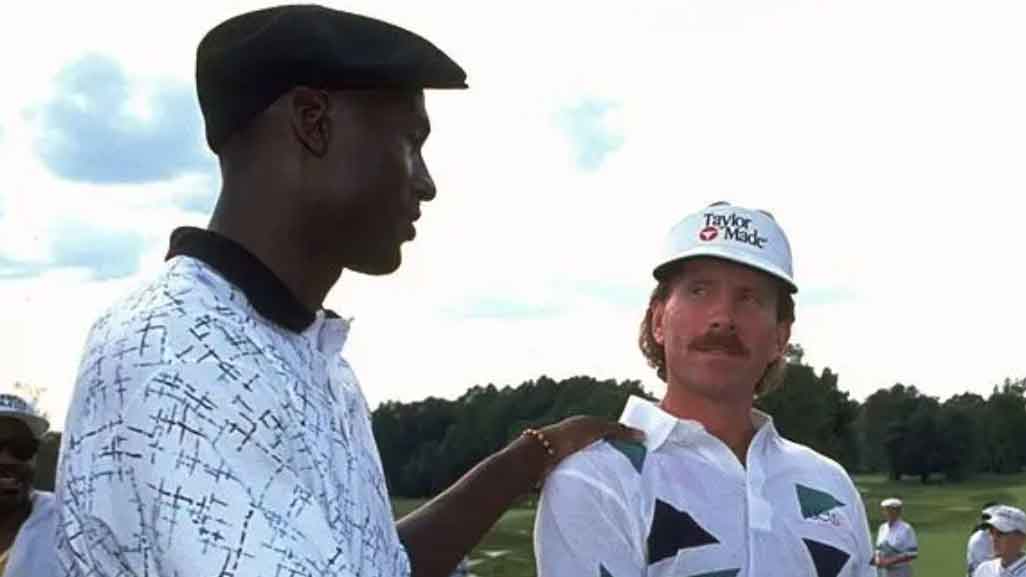

When I asked Schmidt if he could have helped Michael Jordan with his hitting, in jordan’s brief stint in the minor league baseball bush, he was sure of it. “I can teach him to hit,” Schmidt said. Note the present tense, as if it is not late. Schmidt, like Watson, did not lack confidence. MJ, same thing.

getty images

I got to watch Schmidt’s entire baseball career unfold and saw him play golf when he was a 70-shooter. The same guy, really. His approach to both sports was methodical and cerebral. But something he said in our Golf Originals interview really caught me off guard. He talked about how, in baseball and golf, he was consumed by “the mechanics, the worry, the fear of failure.” And when he said that, the player that came to mind was . . . Tiger Woods.

Woods has never delved deeply into his mental state as an athlete. Maybe, when he’s Schmidt’s age, he will. There are obvious outward similarities between the two men. Schmidt, walking to the plate, standing near third base, was never one to worry, to expend energy, to allow himself to be distracted. One of the most memorable moments of the 2019 Masters, in my view, came on Sunday the 17th when Woods was waiting on the fairway watching Brooks Koepka, Ian Poulter and Webb Simpson. Woods stood by his bag, hands on it, barely moving for several long minutes, lost in thought.

But I’ve also thought, watching Woods closely throughout his career, that there were many times when he was filled with worry, confused about his mechanics, afraid that he might fail. I felt like you could see it in his face, and sometimes in his shots. I think Schmidt actually identified three of the things that kept Woods on the practice squad for so long, why he punished himself in the gym, why he almost never relaxed on the golf course. A constant wrestling match with mechanics, a deep and motivating level of uncertainty.

David Feherty on life, loss and his new gig at LIV Golf | Original GOLF

Michael Bamberger

It’s amazing how often, in major championships, Woods would have a near-perfect warm-up session before the round, with Butch Harmon or Hank Haney on his side, and then hit a leadoff drive that went wildly left from wildly right. Woods would find out soon enough. The great ones do. But there were moments he couldn’t handle. Much better to have it on the first hole than the last.

If you play golf with Schmidt and see him take a slow, deliberate walk from the cart to the green, club in hand, it’s hard not to think of the thousands of times he took slow, deliberate walks off the green. on deck in the batter’s box, bat in hand. Then he would have the pitcher in mind. He has it in mind now. Maybe not now, but certainly when he was playing competitive golf in Florida tournaments and on the celebrity circuit. Woods did the same. He walked with purpose.

Woods had, when he was younger, a perfect golf physique, so strong in the core yet so loose. Schmidt, for baseball, also developed a chest that could stop foul shots when patrolling third base, a quick pinch when scoring from second, and arm strength and speed that allowed him to hit 400-foot drive home runs and throw cross country. -bullets on the ground from his knees. The late Pete Rose once said of Schmidt: “To have his body, I’d trade mine and my wife’s and throw in some cash.”

But what I get from our interview with Mike Schmidt, and what you can get from watching it, more than anything, is how level-headed he was in everything he did.

I asked Schmidt if a career in golf would have been as satisfying to him as his career in baseball. He didn’t hesitate: Yes. He thought it would be harder to do in golf, enter the pantheon, as he did in baseball. He would have done it though.

“I would have understood that,” he said.

His smile did not disguise anything. He used to say it. The real big ones mean business.

Michael Bamberger welcomes your comments at Michael.Bamberger@Golf.com.

“>

Michael Bamberger

Golf.com Contributor

Michael Bamberger writes for GOLF Magazine and GOLF.com. Before that, he spent nearly 23 years as a senior writer for Sports Illustrated. After college, he worked as a newspaper reporter, first for (Martha’s) Vreshti newspaper, later for The Philadelphia Inquirer. He has written a number of books on golf and other subjects, the latest of which is The second life of Tiger Woods. His magazine work has been featured in multiple editions of Best American Sports Writing. He holds a US patent for the E-Club, a utility golf club. In 2016, he was awarded the Donald Ross Award by the American Society of Golf Course Architects, the organization’s highest honor.