British sprinting great Linford Christie speaks out AW: about making documentaries, being able to live up to the hype and why he feels unwanted in his sport

During the Paris Olympics, Puma House was a safe haven for athletes sponsored by the brand. Packed with good food and plenty of space to relax, discreetly tucked away in Saint-Denis and not too far from the Stade de France, it was a place to refuel, clear your mind, celebrate or prepare for the challenge ahead.

If any of those athletes needed an expert or two, a number of former stars were also on hand to listen or offer words of wisdom and encouragement.

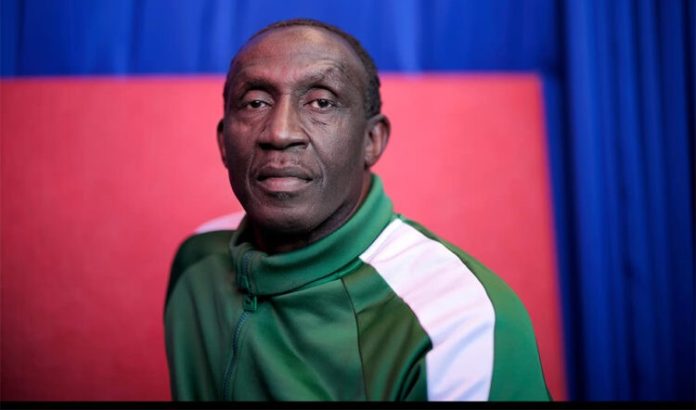

From former 800m world record holder Wilson Kipketer to former men’s pole vault world record holder Renaud Lavillenie, the big names were more than happy to keep company. Among them was Linford Christie, who still has the same distinctive and impressive physique as he did in his Olympic prime.

He’s now 64, but as he chews the fat in the sun with Matthew Hudson-Smith on the day the Brit won his way to 400m silver, the man who once held the Olympic, World, European and Commonwealth 100m titles simultaneously, it seems in his element discusses the sport he just can’t shake.

Listening, watching, learning and being surrounded by athletes is what he still loves to do. Christie moved straight from the track to coaching and has been more than occupied by a group that includes the likes of Paris relay medalist Bianca Williams. However, when he moves to a quiet corner to chat AW:however, he feels like a peripheral person.

Linford Christie (Mark Shearman)

As indicated The latest BBC documentary Linfordhe wasn’t just a journey through the sport. Whether it’s his treatment by sections of the tabloid media or the two-year ban he faced after testing positive for nandrolone in 1999 when he retired from competitive sprinting (he was suspended by British Athletics, but the ban was upheld by the IAAF side), there has been much pain alongside the joy of the 24 major championship medals he has won.

As my colleague Jason Henderson recently wrote athleticsweekly.comthe show is “attractive but uncomfortable to watch.”

The response, Christie says, has been overwhelming and mostly positive.

“A lot of people didn’t realize what I was going through and what I had been through,” she says. “I think it’s good for the next generation to see, and like I said in the documentary, I’m going up regardless. You can never be anything in life if you don’t sacrifice, and to be something you have to go through something. This was me, my sacrifice, and I went through something.

“Do I feel like a weight has been lifted (after the documentary)?” No. To be honest, it got to a stage where I just didn’t care. If you care too much about what people say, you’ll never make it, and I tell my guys (athletes) all the time that I didn’t get to where I am today by worrying about what they say. others about me.

“Your friends need no explanation, and your enemies will not believe you. I just got on with life. Sometimes, of course, it will get to you a little bit, but I’m the person who comes to training to make jokes and all that. If I let something get to me, it sets everyone’s mood. I bear the responsibility of all those people. You don’t have time to let those things get to you.”

Linford Christie (Mark Shearman)

It’s that sense of responsibility that Christie admits keeps her in the sport.

“I love it,” she says. “It’s never going to be 100 percent, but I love it, it gave me something and all I do is give back. It is necessary to continue. I train and there are many times when I think: “I’ve got to quit this, but I’ve got a lot of people’s lives and careers in my hands, so I’ve got to get out there.”

But instead of cutting back, he would also like to give more and get closer to the heart of the action. Having met a number of former champions in Paris, he found that his situation of being held back by the powers that be, be it World Athletics or his governing body, was not unusual.

“It’s a shame the core of the sport, even if I do say so myself, is what they’re missing out on,” he says. “I feel that with my experience I have a lot to give.

“I think they should use me more, but that’s their loss. Winning gold medals, you don’t just go out there and run fast. You have to have a certain mindset and some of these kids haven’t been there before.

GB Sprint Relay Team Seoul 1988 (Mark Shearman)

“I don’t want to be a coach in the team, but to motivate. This is what I do. I’ve never been in a race where I didn’t think I could win and I always tell people I was never the fastest, I just made everyone believe I was.

“I think sometimes people are afraid to hire people who know more than they do, but great leaders… you don’t need to know, you just need to be able to delegate. I don’t want to sit in the stands and watch, I want to sit in the warm-up and learn. But they don’t use us.

“Light running is not a good way to salute the people who have done it. It’s sad, and it’s why we struggle a bit. You can’t worry about the future if you don’t know your past and there is an abundance of knowledge going back. Puma does that by bringing us in so that when the athletes come in, we’re here, they ask questions, (we can) maybe alleviate some of the fears and help. I think that’s what sports should do.

“We need to start doing this in Britain. Bring back some of the old people, because knowledge is key.”

Ron Rodan and Linford Christie (Mark Shearman)

It’s a common refrain from athletes of the past. Christie is highly complimentary of current UKA CEO Jack Buckner and interim head coach Paula Dunn, but he also adds:

“I want to be among the athletes. I go to the (UK) trials and get a little referral that doesn’t get me anywhere. Just as the athletes are invited, they should write to me and say: but sometimes you go to these places and you don’t feel welcome. Many years, if it wasn’t for the athletes, I wouldn’t go. I think a lot of other ex-athletes don’t feel welcome either. We are lucky to have Jack and Paula, what about some of the others? No.”

We’re sitting not far from a room with the big title of Puma’s Innovation Lab, home to some of the latest developments in running, sprinting and jumping shoe technology.

So, I ask, being so close to the super spikes, does Christie wonder what she might do with them on her feet at the height of her powers?

Linford Christie (Mark Shearman)

“Things are moving forward and that’s the future, but I’ve always said it’s not the spikes, it’s the spike man,” said the man whose British 100m record of 9.87 stood for 30 years. “You have to help the spikes help you. I now think that a lot of people get down on themselves (to the point that) if they don’t have spikes or something goes wrong, then they don’t feel like they can perform.

“But things move on and the mindset of the new guys is completely different than the old guys.”

With the help of shows like Netflix’s Sprint series, Christie’s favorite events are returning to a spotlight that has faded since Usain Bolt’s retirement. However, it seems the Brit would have taken some convincing to become part of the TV circus if he was in his prime.

“It makes you say things you shouldn’t,” he says. “You never upset your opponents because you give them 10 percent more adrenaline to beat you.

“There’s a lot of hype now and people saying they’re champions before they’re champions. People like Noah Lyles, on the one hand he’s good for the sport and he gets a lot of attention, but sometimes we don’t want the attention because if you’re the favourite, you’ve got to win. Sometimes you’d rather put pressure on other people than on yourself.”

READ MORE. Documentary Review of Linford Christie

All of the above is why Christie was impressed to see the American win the 100m in Paris after a great race that went down to the top.

“Presentation is what it’s all about,” he continues. “It doesn’t matter what you say, what you’ve done before or what you’ve done, when you step on the starting line, all the slates are wiped clean and you have to start over and do your thing. If you can’t duplicate it, that’s a problem.

READ MORE. Noah Lyles won Olympic gold in the 100m

“It was a great race. I think Keeshan Thompson and Fred Curley thought they had already won it, but it’s never over until it’s over. My coach always told me. “Run 101 meters.” You can see some of the guys start to dive a few meters, but Noah ran all the way. If Kishen and Fred had continued to run across the line, it would have been a different story, but Noah had heart and he wanted it more than anyone. He needed it, and it drove him.’

» This article first appeared in the September issue of AW magazine. Subscribe to AW Magazine herecheck out our new podcast! here or subscribe to our digital archive of back issues from 1945 to the present day here

The post Linford. “To be something, you have to go through something” appeared first AW:.