Calm to the tee? The howler monkeys weren’t having it.

Hiding in the tent above me, the loudest mammals on the planet were charging forward in complete violation golf etiquette: primate with bad behavior and a misleading name. Never mind the nickname. Howler monkeys don’t howl so much as bark and growl at a volume disproportionate to their size. Most stand shorter than your hunter, but their guttural calls can be heard for miles. Think mini Chewbacca with a megaphone.

In a different setting, a rocket on my rear drive might have been a concern. But that’s what I’d hoped for when I booked a date in Costa Rica—a chance to play the game in close contact with nature and all its attendant sights and sounds.

Beyond that, I wasn’t sure what to expect because almost everything I knew about Costa Rica had nothing to do with golf. I doubt I was alone. For those who have never set foot in Costa Rica, the country tends to register as a Wikipedia page, filled with rainforests and reefs, waterfalls and waves, friendly locals and an affordable outdoor lifestyle. It’s all true. Little of it had to do with fairways and greens.

The same characteristics have also made the country a magnet for immigrants. In the inland mountainous areas and along the coast, by the roadside carbonated drinks — humble, family-run cafes that serve married platters and fresh fruit juices—stay within walking distance of yoga studios, surf schools, and the kind of espresso bars you’d find in Santa Monica. This mix of local and imported fuels an economy that was once fueled by agriculture and is now largely driven by eco-tourism.

Conservation doesn’t just help put food on Costa Rican tables. It is also a source of national pride, supported by public policy. About the size of South Carolina, the country covers about 0.03 percent of the planet’s land mass, but contains roughly 5 percent of its biodiversity. Hunting for sport is not allowed. Roughly a quarter of Costa Rica is set aside as national parks or wildlife refuges.

Golf exists too, but in bits and pieces, which makes sense given the numbers. There are only about 2,000 registered players in a population of 5 million, and roughly a dozen fields, some of which are little more than makeshift backyard structures. Older clubs, such as the Costa Rica Country Club, are clustered around the capital city of San Jose. But for most visitors, the game unfolds on the northwest coast, around the Papagayo Peninsula, where freeways divide space with jungle and ocean.

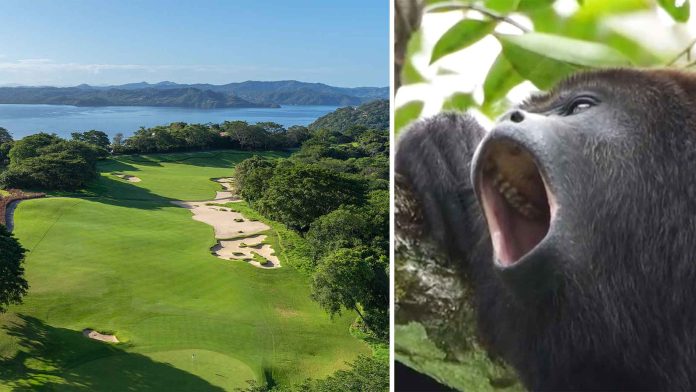

The peninsula, which overlooks a bay of the same name, is a mosaic of steep headlands and hidden coves, with resorts stitched into the slopes. The Ocean Course at the Four Seasons snakes along the coastal bluffs, its holes laced to showcase views at every turn. You drive from the green to the top, emerging into spaces with stunning panoramas.

The scenery comes with a cast of local characters. By the time I made the turn, the morning chorus of howlers had fallen. Near the club, however, I saw a different type of monkey – a white-faced capuchin – raiding someone’s cart with food unattended. Moving to the back, I saw two bucks, antlers locked, fighting for the attention of a watching doe with what I could have sworn was slight embarrassment. An anteater ran through a railing next to the cart path – a flashy show and you’ll miss it.

When I wasn’t on the course, I did what golfers do best between rounds: I rested, but just enough to restart for other activities. Andaz, where I was staying, offers snorkeling, paddle boarding, and an eco-zip line cut through a nature reserve: a trapeze act for mindless Tarzans. (There’s more to come. Next month, Papagayo Peninsula will cut the ribbon at Papagayo Park, a lifestyle center equipped with a pump track, lap ball, lap pool, fitness platform and more, all available to guests and residents of the Andaz, Four Seasons and Nekaui, a Ritz-Carlton Reserve). Another way to visit the treetops is via a canopy walk along swinging boards and rope ladders. From one of those high vantage points, I finally got a close-up look at one of the cacophonous culprits I’d heard on the course: a howler monkey, leaning against a branch. My guide told me that they spend most of the day nibbling on fermented fruit, which lets them rest with a gentle hum, but not so gloomy as to remain mum.

“So they’re loud and lazy, like my kids,” I said.

Deep down, though, I was feeling jealous, not judgmental.

That evening, I enjoyed some cocktails myself. But in the morning I was ready to connect it again. A short drive around the coast brought me to Reserva Conchal, a Robert Trent Jones Jr. design. which began life as the Lion’s Reign and retains a wonderful ferocity. The road passes through trees, edges lakes and borders a mangrove forest that doubles as a wildlife corridor. Iguanas roamed the freeways. Toucans flashed overhead.

My playing partner was the resort’s director of golf, Carlos Rojas, who got into the game caddying as a kid near the capital and never looked back. Bursting with energy—a vivacity he credited to his carnivorous diet (“No sugar, no carbs,” he said. “I’m never tired, ever”)—he struck me as the joyful embodiment of clean lifeclean life, a phrase that serves as both a greeting and a kind of national slogan. While they eat almost nothing but red meat, Rojas oversees a course that’s as green as it sounds: reclaimed water, 100 percent organic fertilizer, composting, and even tees and ball markers made from recycled coffee grounds.

;)

Josh Sens

Golf in Costa Rica is not widespread, but what exists fits perfectly with the country’s ethos: small-scale, sustainable, in sync with nature.

Back at the Andaz that evening, the jungle was alive with sound again. From the terrace, I heard howlers calling through the canopy—a racket, yes, but strangely soothing. They were still chatting at dawn as I returned to the Ocean course for a quick round before my departure. When I found the freeway with my pitching car, I imagined the sound coming from the trees was cheering.

I’ll take it over Baba-booey, any day.