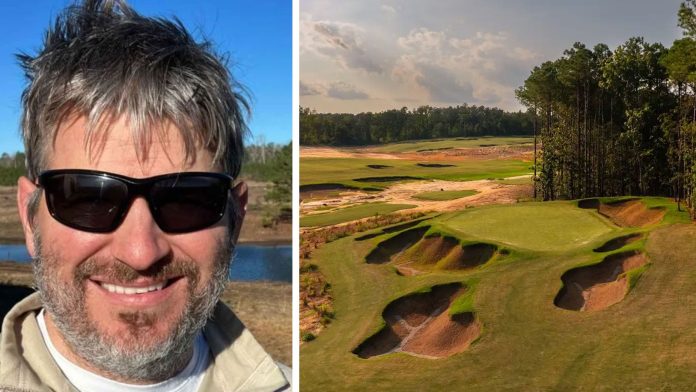

Mike Koprowski’s dream has come true in the form of Broomsedge Golf Club, in the Sandhills of South Carolina.

Carolina Pines Golf (left); Broomsedge

If you’ve always dreamed of building and owning a golf course, here’s a way to finally make it happen: make a fortune on another course, then pour some of that income into your passion project.

This approach worked well Dick YoungscapHerb Kohler and Mike Keizerwho gave the world Sand Hills, Whistling Straits and Dunat Bandonrespectively.

But maybe those developers don’t consider you as similar models.

In case you belong to a lower income group, a more inspiring example can be Mike Koprowski.

Koprowski, who is 40 years old and married with two children, is a jack of all trades and a longtime golf junkie. But he’s not a one percenter, and until a few years ago, he had never worked in golf.

And yet he made it happen. In a middle-aged pivot, he bought a tract of land at a manageable price, put a shovel in the ground and did a feat usually reserved for multi-millionaires.

“People with no money don’t usually start golf developments, so I guess you could say this is a little bit of a different story,” Koprowski said the other day by phone from the Sandhills of South Carolina. He was sitting on a tractor at Broomsedge Golf Club, the soon-to-open course he owns and co-designed. “Sometimes I have to pinch myself to confirm it’s real.”

Courtesy Broomsedge

Koprowski’s fantasy come true was born out of childhood dreams in South Florida, where he learned the game early from his father, a former captain of the Notre Dame men’s golf team. Young Mike did very well. He competed in high school. But what really impressed him was the course design, an interest sparked by a round he played on the Stadium Course in TPC Sawgrass. Amazed by Pete Dye’s work, he received a copy of “Bury Me in a Pot Bunker,” Dye’s memoir of his life in golf course architecture.

“I just thought, ‘How cool is this?'” says Koprowski. “It seemed like something I would really like to do.”

Instead, he went to college, like his father, at Notre Dame, though not to join the golf team. He washed his chopsticks, signed up for ROTC, and studied history and political science. There was no golf after graduation, either, as Koprowski enlisted in the Air Force for a four-year stint that included a tour of duty as an intelligence officer in Afghanistan. His game was rusty. But he emphasized other skills. In what now seems like a preface, Koprowski says, “I’m pretty good at reading topographical maps.”

Back in the U.S., post-military service, Koprowski compiled a stellar resume, earning master’s degrees from Duke and Harvard, respectively, in international relations and education, before moving on to posts in public schools and housing policy in Tennessee. Texas and Washington. DC By then, he had taken up golf again and his interest in design never left him. He even went so far as to build a short par-3 outside his home in Nashville, a front yard project that a glossy golf magazine featured in its pages. Otherwise, though, the only holes Koprowski created were in his head.

“On every road trip, I was the guy looking out into the desert at a ridgeline to see where the green would go,” he says. “What I couldn’t see was how I could make it a career.”

The change came in the way one of Hemingway’s characters broke down: gradually, then suddenly. A combination of factors figured in the change. In 2018, living in DC but fed up with Beltway politics, Koprowski was ready for something different. His wife was about to start law school. Meanwhile his father had retired to Pinehurst.

“The idea that we could move and be closer to family made a lot of sense for a lot of reasons,” says Koprowski. “And the fact that it was a move to Pinehurst meant you didn’t have to turn my arm at all.”

At the time, architect Kyle Franz, having recently restored Pine Needles and Mid-Pines, was about to do the same on another local Donald Ross project. Southern Pines Golf Club was going under the knife. The fact that this was happening in his new backyard struck Koprowski as a sign.

“I decided it was now or never,” he says.

Courtesy Broomsedge

He emailed Franz out of the blue, asking if he could come work for free. As in other trades, such requests are not unheard of in golf course architecture circles. Indeed, decades earlier, as an eager 19-year-old, Franz had sent a similar message to Tom Doak while Pacific Dunes was being developed in Oregon, and Doak had found a place for him on the project.

“In a way, Mike reminded me of myself when I was younger,” says Franz. “But it was also clear that he had a different background. I checked his LinkedIn. Duke. Harvard. Those political affairs. And I thought, well, dang, this is a very smart guy.’”

Within days of their initial correspondence, Koprowski was out in Southern Pines, getting his hands dirty. At Franz’s insistence, he also earned an hourly wage. At first, it was only weekends, as Koprowski was still working remotely on his policy work. But now that he was headed in a new direction, there was no looking back.

He had a lot to learn. Having pondered this subject for most of his life, Koprowski had a good grasp on the principles of good design. What he didn’t have a handle on was mechanics. “That’s what I had to learn,” Koprowski says. “How do you execute it on the ground.”

Southern Pines was a crash course, a soup-to-nuts education in everything from soil sampling to molding. Koprowski turned out to be a quick study.

“He did a little bit of a lot there,” says Franz. “And with all his other training, he knew Google Earth backwards and forwards. He was adept at reading maps and summarizing ideas into proposals. He was an asset all around.”

Southern Pines gave way to Franz’s other projects – Cabot Citrus Farms in Florida; Eastward Ho in Massachusetts – enough opportunity for Koprowski to leave his old job behind. He was now employed full-time in the course design business, living his dream, with a fantastic unfulfilled ambition.

For as long as he could remember, Koprowski had been drawn to the story of George Crump, the Philadelphia hotelier and golf fanatic who, in the early 1900s, bought property in New Jersey and set in motion what would become Pine Valley – such a quixotic project. that some referred to it as “Crump’s Folly.”

“I’ve always been fascinated by it — the idea of owning and building a golf course,” says Koprowski. “What a fun and funny thing to do.”

Silly, perhaps. But it required serious commitment. And nothing could happen without land. That was the bad news. The good news was that the same sandy soil that made the Pinehurst area an ideal canvas was spread throughout other parts of the Carolinas. Setting his sights on the Sandhills east of Columbia, SC, where great golf, he said, was relatively scarce and real estate more within his reach, Koprowski looked at dozens of lots before finding one that suited him. billing: 197 hectares with the right. amount of movement, in the market for the right price.

Courtesy Broomsedge

Interest rates were low. Koprowski’s confidence in the site was high. His optimism grew further when Franz saw land and shared his excitement. In short, Koprowski secured a loan, put together the funds for a small down payment, and took the property for $630,000.

“My plan was to find a way to cover the monthly payments until we figured things out,” he says. “And if we didn’t, then I could just go back and sell.”

The catch, of course, was obvious. Now that he had the land, he had no money left to do anything with it. He needed proof of concept to present to investors. Even before finalizing the purchase, Koprowski had mapped out a possible path. That was something. But he had to do more. With the modest support of the angels, Koprowski got his permits and cleared some trees. However, the construction costs were far beyond his means. Caught in a deadlock, Koprowski decided jumping into a dozer was the best way to break through.

“Part of me thought if I started forming some greens, maybe I could get some investors to come on board,” he says.

He was right. The first major backer to come on board was Cody Sundberg, an accomplished amateur golfer from Illinois with a background in finance and real estate. The others followed. That was two years ago. Broomsedge Golf Club will be ready for play this month. A rapid progress. Not that there weren’t bumps along the way.

“I remember the days in July sitting in the excavator with the air conditioning broken, doing a rough shape while we had about $82 in the bank without the knowledge of the investors,” says Koprowski. Close friends warned him that he would lose his shirt. “There were some dark moments when I didn’t think it was going to work,” he says.

With each new investor, Koprowski sold shares in the project, and now he is a minority owner. But the vision for Broomsedge remains his. He and Franz share design credit for a course that cuts the profile of rustic charm, with an intimate fairway filled with strategic options, its fairways surrounded by sand waste and the wild native grass that gives the club its name.

“One of the many things that stands out to me is the courage it took to do this,” says Franz. “This is not the first time that a shaper or an aspiring architect has had the idea of finding a piece of land and building a course. The difference is that Mike actually went ahead and did it. He had a stomach for danger.”

Although Broomsedge is private, Koprowski has taken a page from Sand Hills developer Dick Youngscap, which allows outsiders to play his well-known Nebraska course once if they seek approval through a letter of introduction.

“My dad and I got to play Sand Hills that way, and it’s always stuck with me,” Koprowski says. “I have a lot of affection for the model (Youngscap) created there and the idea that it gives everyone that special opportunity, even if it’s just once.”

Not that he would put himself in Youngscap’s league. Nor would he be so bold as to draw too many parallels between himself and Crump.

For one thing, Koprowski says, “Crump built what is arguably the greatest course in the world, and while I think Broomsedge is a great course in its own right, I don’t see it stripping Pine Valley of that title.”

And here it is: Crump died tragically at the age of 46, with only a few holes of his dream project completed.

“I think that’s another difference,” Koprowski says. “So far, it’s been a happier tale for me.”