The sun has plunged down the horizon in Long Island and the street lamps in Bethpage State Park The lot of the car falls into life. The club’s house is quiet. The latest golf carts are rejected and stored, the rod of the snack closed and the fairways are emptied. Another summer day is in the books in the most busy muni and perhaps New York’s boyfriend.

In just a few short months, Bethpage’s black course will wait Ryder cupThe team’s latest event in Golf. Grandstands already raised over the greens on this sad night in mid -July. Temporary hospitality structures grow as scaffolding around the streets of the fair. By the end of September, this piece of New York will be the center of the Golf Universe’s hit. But tonight, the only buzzing is coming from an posterior corner of the parking lot. Nearby, America’s “Ryder Cup Operations” PGA trailers sit dark and closed, but not far from real action is developing.

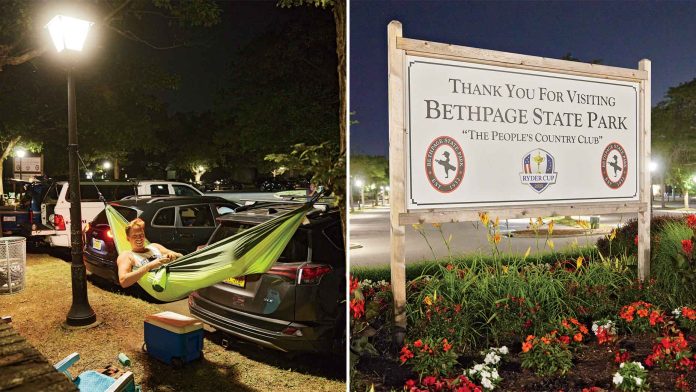

Thirty plus cars are resting on the semicircular part, each lined up after a painted number. Camp chairs, tents and coolers drip Blacktop. A man lies on top of his SUV, looking at the stars. Another strings a hammock between the two strips, drinking a beer and laughing with a shock sitting close to a sword.

Near the marked space no. 1 – a coveted place overnight – six men lies in vain around a coolant as if it were a campfire. A pizza distributor arrives with a pin stack in white square boxes. If it feels and looks a lot like a hanging football college, there is a critical difference: these people are here play; To follow a great deal of time and treat the black course, which attracts golf diehards from all over the country for a stroke in one of the most difficult game tests.

Black’s black leaf, for years, has been filled almost every day, but, with the close arrival of the Ryder Cup, the demand has reached an even more thirsty pitch. Since the beginning of July, the course has only accepted time to walk, meaning that there is only one way to provide a round: off -night camp in the parking lot. In fact, it is a ritual dating back decades.

Steven Ji, a 73-year-old Korean American who lives not far from the park, first played black in the early 1980s. In the years since then, he estimates that he has drawn it on the course over 600 times. Still, here he is, on a foggy New York night, connecting and becoming bad with Bros.

“USA! USA! USA!” Be cheering, pumping his fists in the air as the conversation moves to the Ryder Cup. “That’s culture,” he adds quieter. “You come early. You camp out, you like time. It’s not just golf – it’s Bethpage.”

One of those who withdrew in the patriotic joy of Ji is Brandon Johnston, the lucky occupier of no. 1. His small gray sedan anchors the queue and reduces it first in a great deal of time in the morning. The 29-year-old made a two-hour journey from Central to New Jersey, reached the draw at 9am and was fired from his car a makeshift work station, a folding, laptop, monitor and all.

“I wanted to try to work that I could still be productive,” he says in a fuss. “I’ve done some things. Much of my work is on my phone, so it’s manable.”

Bethpage adjustment reservation system to fight bots in time

James Colgan

The youngest in the Jabbers district is 18-year-old John Classsen. He and his father, Peter, traveled 10 hours from Virginia to bet in a black time. Fresh from high school, John is taking a year of gap to check as many buckets as possible. This tops his list

“I’ve dreamed of this,” he says. “I’m just very happy now, nor do I think I’ll sleep.”

He puts his concern to be used, connecting to a triple of 20-time from Philadelphia that will now finish his quadrilateral. Their goal: the earliest available time, so John and his father can do it again in Virginia after the round.

But for hours to go before sunrise, there is time to kill. They grab their circles and hit the green practice for a competition located under the brightness of a dozen street lamps.

“Which parent would not want to support this kind of thing?” Says Peter. He is not playing black, but he plans to walk every hole with his son, documenting the experience as they go. “He’s not just playing golf. He’s linking. He is building memories. He’s doing something different. I’m proud to be part of it.”

On the other side of the club, the infamous black warning sign is even more ominous in the moonlight. John will not steal a look tonight. “I’m saving it,” he says. “I want to be in that first tee and just look at how, how, Wow.“

With the dimming of their adrenaline and the late night winding, the group-one of the one is directed to their cars. Awaits 7,500 AW tilinghast, and they will need the whole kip they can get. But sleep does not come easily. Temps extend close to 90 degrees; The legs hang on the truck beds; Heads rest against cracked windows; And dreams move to birds made in the footsteps and goods that have been competing here since 2002.

From 4am, the wait is almost over. The tear begins to stir. Open cars doors; Silhouettes lie and yawn; Golfists go out, staring at the dark. Ryder Cup Ficker operations trailers and trailers and a state park companion unlocks the carriage barn. Four gather in front of their cars, waiting for Park Ranger and John Deere Gator to appear. It finally does and begins the rolling call, submitting Brandon Johnston’s tickets and his group labeled “1.” They jump into their car, start their engines and make a beeline for the club 150 yards away. Classrooms are another, followed by children by Philly.

A line is formed outside the club. An employee of Bethpage stands at the door, calling numbers one by one and letting players record their dream round. Brandon appears first, radiating. He and his fourths have sewed noon for a while and plan to go to a nearby friend’s home to catch a few hours of sleep. John and Peter appear next. They collided by 8:40 in the morning they will hang around the parking lot, waiting for the course restaurant to open.

Soon, the sun begins to rise above the Long Island, washing the course in the pale orange light. One ground holder cuts a fresh hole in the 18th green while another guides a mower down the straight path. Only alongside the first Tee, a group of teens of the Sullen sit on a bench, seeing the day unfolds and the construction of Ryder Cup grows will be every day for the coming months.

“I can’t believe we’ve arrived here at 3am and still haven’t taken a great time,” one of them groan.

But perhaps their annoying fate is poor luck. The first cars for tomorrow’s line have already begun to arrive.

;)