Sean Zak

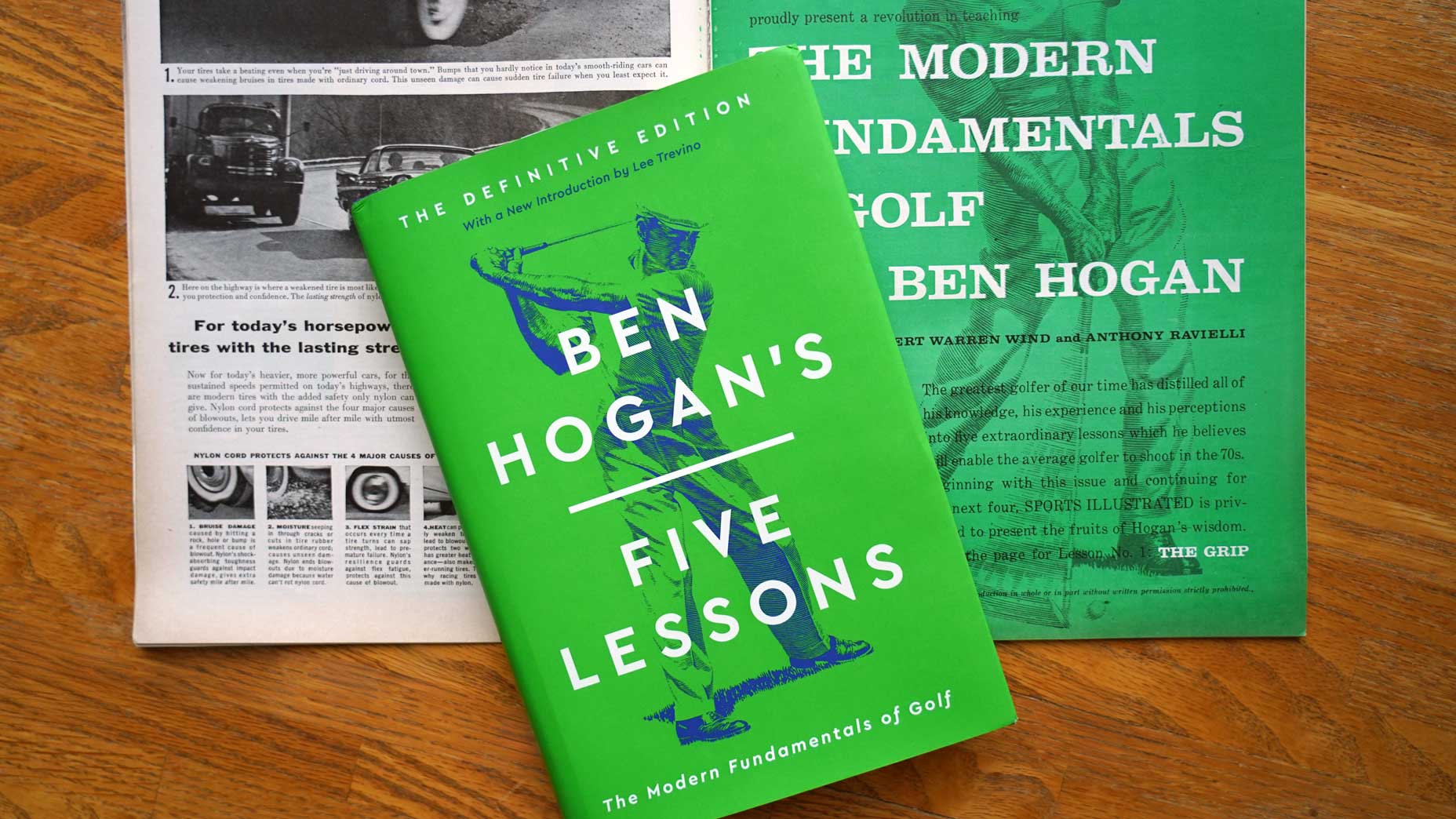

The new “Five Lessons” edition has an electric green cover, a nod to the Sports Illustrated article from which it was created.

Sean Zak

When it comes to golf books, publishers believe in two absolutes. First, golf literature generally sells better than literature on other sports. The endless game is so connected that it is enough readablealso.

Second, golf books are routinely published only a few times a year: April, around the Masters; mid-June, to coincide with Father’s Day and the peak of the golf season; and during the holidays, when the perfect socks are a ball sleeve and a $19 pocket square.

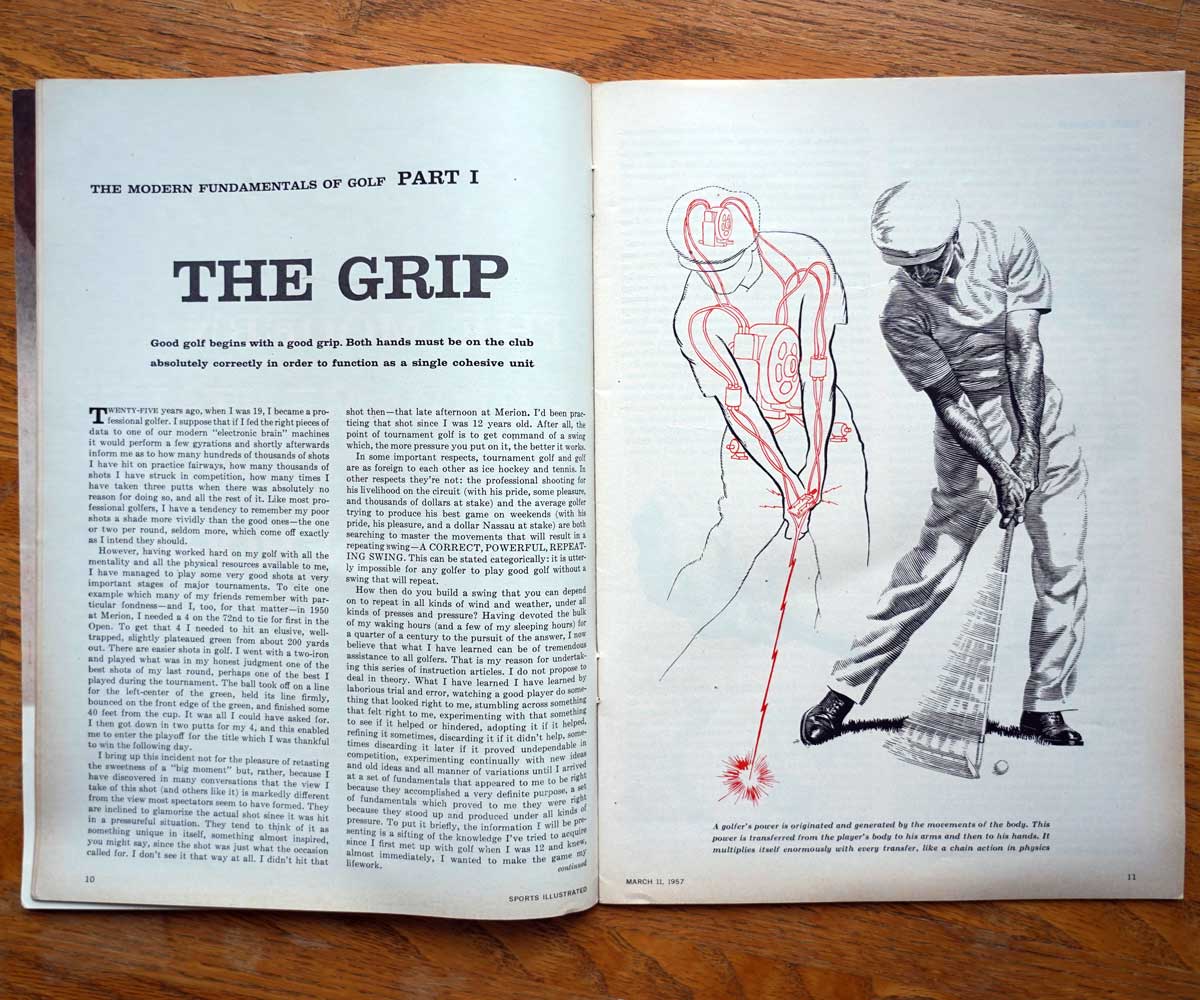

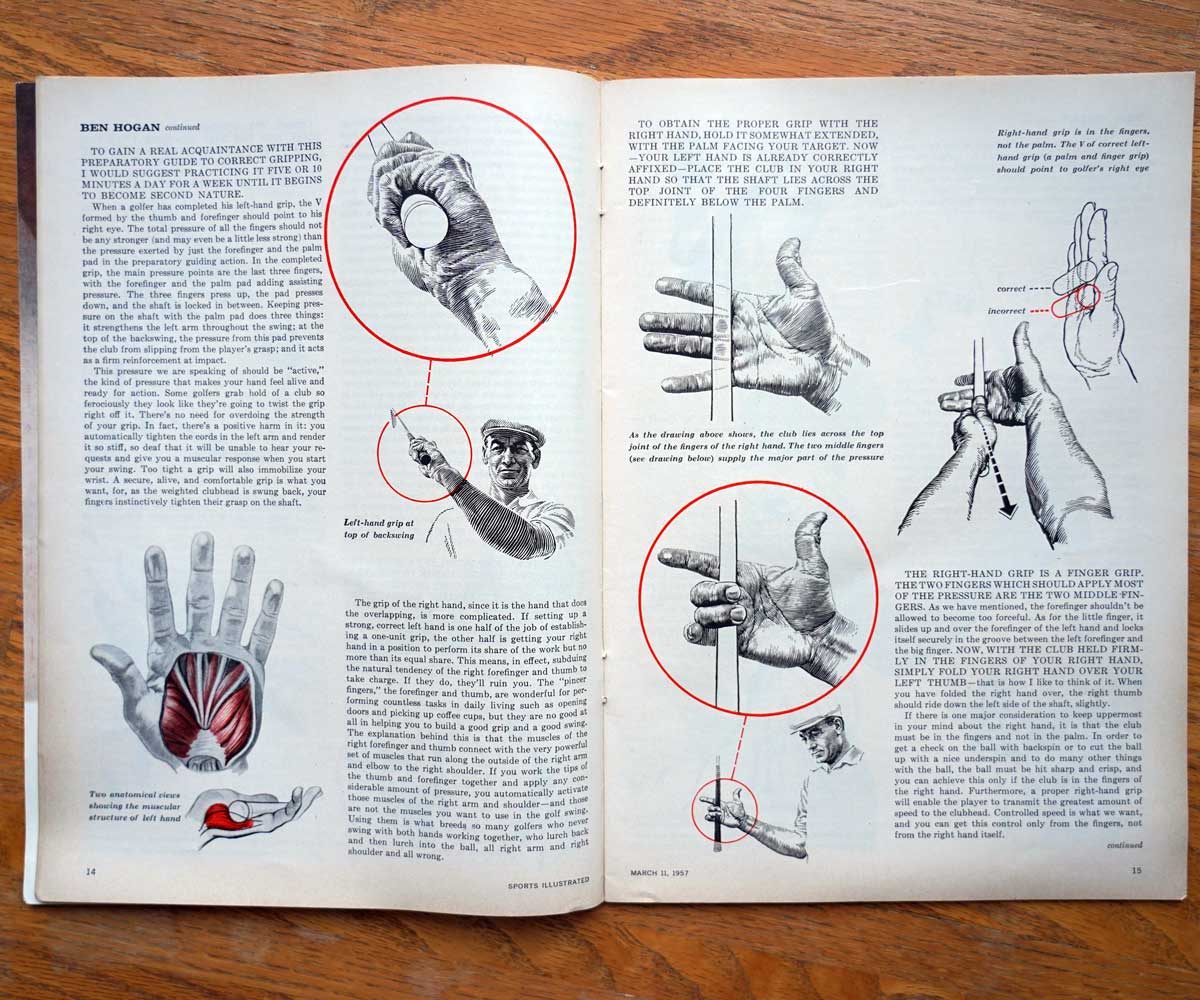

Reviewing the best golf books on Amazon, however, may leave you puzzled. The best-selling golf book today is the same best-seller three months ago. And three years ago. And, yes, even three decades ago. It’s Ben Hogan’s Five Lessons, first published in Sports Illustrated in 1957.

Not only is the print edition consistently ranked in the top 5 golf books – often at no. 1 — but the Kindle version is often in the top 25 as well. Last weekend the audiobook ranked at number 58. Most titles just want A Hogan’s wisdom—as told to legendary golf writer Herb Wind and illustrated on the board by Anthony Ravielli—continues to be widely used in every medium. If the Rules of Golf are the sport’s 10 Commandments, then this book is the closest thing there is to a Bible.

A common question accompanies this idea: Should it be?

That depends on who you ask. After all, many 12 handicappers get bogged down in the complex differences Hogan details between supination and pronation. A better question then is HOW has the book held up over time? Apparently, every elite professional of the 20th century had a guidebook, or several, to their name. Watson, Nicklaus, Trevino, Palmer, Snead. How and why did Hogan himself split?

John Garrity had a better look than anyone. Before a long career in golf he beat in Sports IllustratedGarrity was an associate editor at Simon and Schuster in the early 1970s, where how-to books, it was said, were almost always given the green light. The books didn’t cost much and didn’t make much money, Garrity says, but they also never lost money. They all seemed to sell about the same number of copies – 12,000 – regardless of who graced the cover. “There have only been a few exceptions to this,” Garrity said. “Ben Hogan’s ‘Five Lesson’ is the biggest seller.”

The way more.

Estimates by industry experts—the manuscript has been licensed to dozens of publishers over the years—put the number of copies sold at more than a million. And counting. This week, Simon and Schuster published a 40th anniversary edition of the book, leaving the original text intact but filling it with a new foreword by Lee Trevino and adding 97 new pages of “History, Context, Legacy “. The new and improved Five Lessons is bound in a bright, electric green cover, a nod to the palate of the magazine’s original layout. AND published those five lessons in installments, in five consecutive issues, during the magazine’s launch in 1957.

Ben Hogan’s Five Lessons

29 dollars

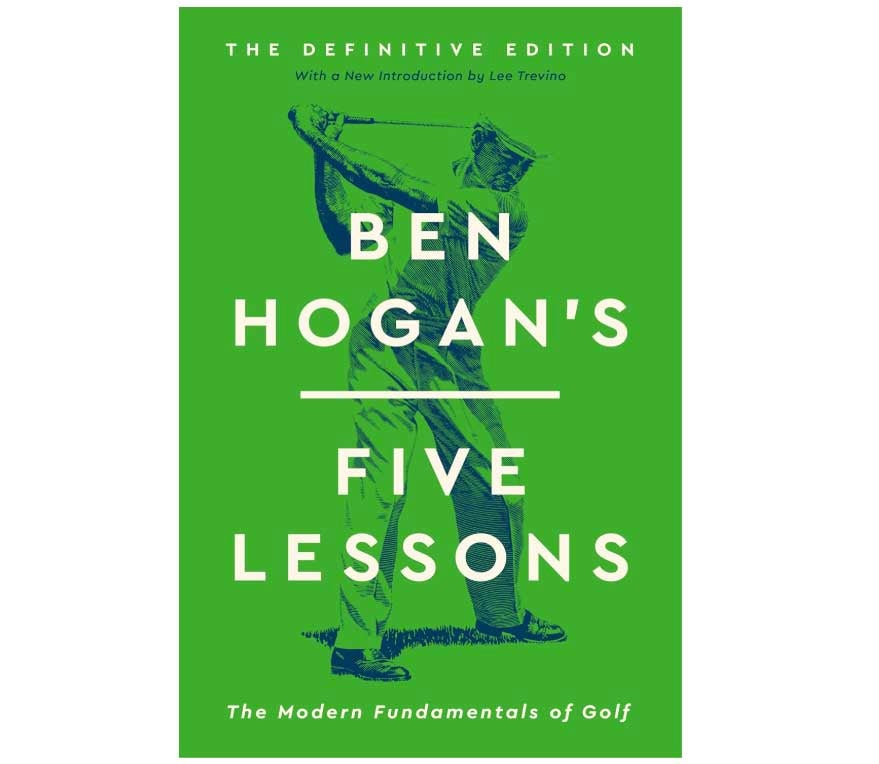

With a new introduction by Lee Trevino, this is the first definitive edition of the timeless golf classic that has sold over a million copies – now with never-before-seen photos and memorabilia hand-picked from the Hogan estate archive , as well as nearly 100 pages of new writing expanding on Hogan’s incredible life story and remarkable career.

Buy now

Simon and Schuster editor Jofie Ferrari-Adler worked with longtime golf writers Michael Bamberger (a GOLF.com contributor) and Jaime Diaz to breathe new life into the work of Hogan, Wind and Ravielli. What they created is like a literary museum exhibit. The 67-year-old artifact is the main event, but it’s now accompanied by a very rich context about the men who crafted it. There are game stories from the 50s, columns from the 90s, and even an interview between Hogan and Ken Venturi from a 1980s CBS broadcast. The new edition is an ode to Hogan, of course, but also to one of the game’s greatest writers on Wind; the book includes some of Wind’s greatest hits, compiled by the next generation of writers.

But none of this explains it why the book remains so popular – or became so popular in the first place – especially with the advent of digital golf instruction, most of which can be personalized and delivered via the big screen in your living room and the 6-inch screen in your pocket.

Like any old recipe, Five Lessons’ staying power is fueled by its ingredients. You had the best ball striker of his generation combined with the best wordsmith of his generation. (Ravielli, the illustrator, was not the third wheel.) The compilation took 10 months to complete, but it landed in a boom period for recreational golf. Right after AND published the lessons, the magazine’s editor wrote that Hogan’s ideas had been so popular that readers were tearing out the pages AND replicas at the Yale Club and golfers in the snowy Northeast couldn’t resist hitting the driving range right away.

Sean Zak

Sean Zak

Perhaps the best modern account of Lessons’ success is ESPN’s The Last Dance documentary, which revealed many of Michael Jordan’s thoughts on basketball and his career for the first time – and on perfect time, when the world was sheltering at the height of the Covid-19 pandemic. We were all home and hungry for new content, and Jordan, as Hogan, was closer than ever. Hogan, like Jordan, was long believed to possess something special, but rarely discussed his talents publicly.

“I think it’s really the mystique that sells the book,” said Jaime Diaz, “because Hogan was such an extraordinary genius and so inside and reticent to ever talk about anything since he finally did , it was like, Oh my God, the safe has finally been opened.”

The tips themselves are dense. Nineteen pages devoted to just catching the club. Twenty-five at takeoff. The writing is authoritative, bordering on discourse, with the occasional clause in capital letters and lots of italics emphasizing what the golf genius NEEDS you to focus. The ultimate goal, in Hogan’s mind, was for cheating players to consistently break 80. But the ultimate ideology of the book is quite simple: never hit it.

“It’s an anti-hook book,” Diaz said. “I mean, really poor control and just making sure the club never comes back. It’s a Tournament player’s swing. But even Tour players can’t always repeat that.”

Herein lies a truism of the game. No single set of lessons can solve the golf puzzle of the unlimited number of body types and abilities we see on a driving range, even a PGA Tour driving range. (As Arnold Palmer preached, swing your swing!) This idea, all these years later, is repeated far ahead, in Trevino’s preface. In the first five pages, Trevino turns back the clock to 1957, when he crashed magazine while on a Marine Corps ship bound for Japan.

Even Trevino admits that he “may not have understood everything Mr. Hogan and Mr. Wind wrote, but their words furthered my golf education.” Trevino joined the Marine Corps golf team overseas and played harder than ever. After his discharge, he practiced on his own with two golf balls—one his score, the other Hogan’s. A few years later, Trevino visited Hogan’s club, Shady Oaks, in Dallas; he was shocked by Hogan’s body movement, memorizing how Hogan’s hips directed his action. As Trevino writes, “That’s when I started getting better.”

For Trevino, Hogan was inspiration and imagination. And isn’t that how golf is feels for all of us? If we’re looking for anything in this game, it’s kind of it smeltcooked up in our imagination or inspired by something. Or someone. Trevino’s fly ball became a fade, like Hogan’s, but it didn’t look like Hogan’s fade at all. Trevino had taken The Modern Fundamentals and made them his own.