The only recent result that really speaks to where Joshua is as a heavyweight is still the Dubois beat at Wembley – dropped early, legs gone, stopped in five as he tried to trade his way out instead of finishing the fight. The Ngannou knockout before that gave him a high, but it didn’t solve the same old problems: straight-line takedowns, freezing under sustained pressure, and leaving his chin in reach after throwing.

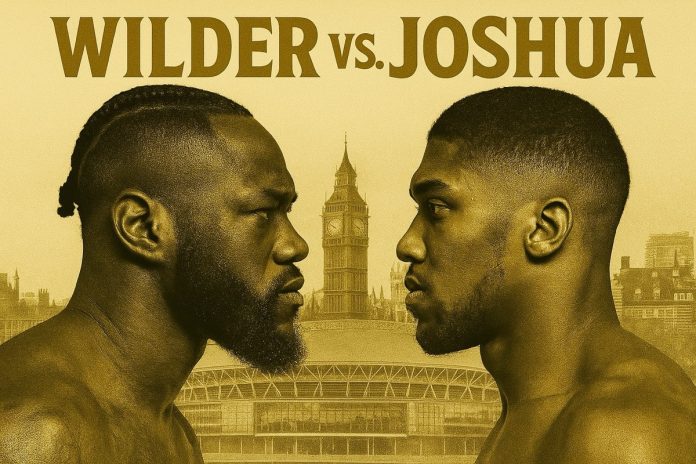

Wilder’s “we must meet” line and what it really means

Deontay Wilder says “we have to meet“Sounds like doom talk, but the context is a 40-year-old with a 1–4 stretch since 2020 and a tune-up about Tyrrell Herndon being sold as proof of life. That Herndon fight was roadwork under lights: Wilder dropped a willing craftsman twice, got a few rounds in when his right hand cracked and is still cracking authority with his right hand.

The quote is less a great calling and more a man looking for one last jackpot while his name still rings. “We’re both still in this business” translates to “we both still have value on a poster,” not “we’re at the top of the food chain.” A trainer who listens who hears urgency, not confidence

What could go wrong for Joshua?

Stylistically, Joshua has always been vulnerable to the exact thing Wilder still does better than almost anyone: long, fast right hands thrown off broken rhythm. Joshua likes neat phases – jab, jab, right hand, reset – and when the pattern gets messed up, he tends to stand up, hold his feet too long and try to answer instead of killing the exchange, which is exactly when Wilder’s right comes out on top.

The Dubois loss showed Joshua still doesn’t manage panic rounds well: He got hurt early, never really got his legs back, and tried to stand his man when he needed to choke, clinch and take the air out of the fight. Against Wilder, one ego moment like that – staying in the pocket half a beat too long to ‘send a message’ – is how a fight he controls suddenly becomes him staring at the lights.

What problem does Wilder actually pose?

Even faded, Wilder’s threat is simple and ugly: he can lose every round and still turn the whole thing around with a single right if he can lure you into overhanding. Herndon showed his timing isn’t completely gone; he still found the distance when the other man’s output dropped, and once he saw the opening, he didn’t need many clean touches to force the stoppage.

The real danger for Joshua is mental tempo, not physical damage build-up: you can box neatly, bank rounds, then get greedy and throw one combination too many because you’re bored of winning on the jab. Wilder’s entire game is now built around that bad decision – slow fight, low volume, then a sudden sprint into a thoroughbred just the moment your discipline drops.

Which this fight exposes instead of proof

Joshua–Wilder in 2026 settles no mythical “era” debate; Fury, Usyk and Dubois have already written that history. What this exposes is whether Joshua can go twelve rounds without unraveling mentally when real power is in front of him again, and whether Wilder has enough legs and timing left to even create a real finish opportunity, not just wing hopeful rights from too far out.

The match also shows how both men handle risk when there is no belt on, just prize money and reputation. Take away the excuse of obligations and unquestioned politics and you see who still wants to step into a ring with their chin on the line purely for pride and a check.

Business, timing and what is actually possible

Usyk holding the big belts means this is a pure box office fight: no sanctioning body forcing it, no mandatory clock ticking, just whether the Saudis or an American network thinks there’s enough juice left in both names to justify the guarantees. The Paul numbers – 33 million global viewers on Netflix – give Joshua strong leverage; his side can argue that they don’t need Wilder to sell out arenas or drive streaming traffic.

For Wilder, there is no bigger payday left than Joshua; Usyk would be high risk, lower reward from a spectacle standpoint, and the heavyweight contenders don’t bring the same money. This is why you hear “almost certainly I will fight Joshua” — it’s not vision, it’s economics.

If it goes wrong

If Joshua signs Wilder and gets knocked out, staggered and bailed out, whatever – he’s no longer talked about as a guy who can come back for titles and becomes an expensive name for crossover events and prospects who want a scalp. A second violent loss in two years, on top of the Dubois collapse, will tell every heavyweight in the top ten that if you can make him think and hit at the same time, he cracks.

If things go wrong for Wilder – if Joshua walks him into a systematic beating, or even just rounds and then lets him finish once the legs are gone – the “one punch away” myth dies forever and he moves to pure nostalgia: highlight reels and guest-of-honor roles, not live dog status. Either way, this fight, if it happens, doesn’t rebuild careers; it closes one of them for good.