In an extract from his honest and insightful autobiography, the Irish Olympian recalls the aftermath of winning European 400m gold in 2005.

Sports can be so volatile, with fractions of a second separating roaring success and abject failure. The difference is how they are taken. Win a medal and suddenly.

The media is all yours. Cross and it’s a lonely, nameless walk into the night. I was suddenly in high demand that Sunday morning in Madrid, and my first meeting was with an Irish photographer who took me to a location in the city to pose with gold. While waiting in the hotel lobby, people from different nationalities came to offer their congratulations. Then there was the buzz of flying home. It was the most surreal part I had flown into Madrid as a complete unknown to most of Ireland. But the win made national headlines.

When our plane landed in Dublin, I was taken to the front and asked to wait a few minutes while they opened the doors. As they did, I saw a group of people waiting and a boy playing the bagpipes. I was just there, watching Mr. Baggage as we walked through the airport, heads turning all around, and I was embarrassed. I went to get my bag and was told not to worry about it and there was another crowd in the arrivals hall with lots of club mates, friends and relatives. One of my friends had a big sign saying, Gillick, Will You Marry Me?

Over the weeks, I heard countless stories about the excitement the race gave people. Friends of friends told how they were roaring on their feet at the TV. That was always what I did when I watched Irish athletes or teams. It was strange, surreal, to hear other people say they did it for me.

At home, our landline was flooded with calls, my mother sifting through the messages. Letters were dropped home, with various people congratulating.

But when I took a step back and had a few moments to think, one question loomed: What do I do now?

I returned on Monday and went to a reception that night at a local pub. But by 9am on Tuesday morning I was back lecturing at the Dublin Institute of Technology. That’s exactly what I wanted. to resume normal life as soon as possible. But that was easier said than done. I boarded the tram to head downtown, but immediately felt that something had changed. People looked at me, noticed me. I sat next to a guy who was reading a newspaper and out of the corner of my eye I saw that he was reading a story about me. After a while he looked up, then back.

“You…

“Yeah,” I said awkwardly.

‘Oh, Jesus! Fair play to you.

In college, one of our professors announced my win in class, even though most of them already knew about it. For days, weeks, months there were reminders that now everything is different.

For example, three days after coming home, my friends and I went to the most popular nightclub in Dublin, Copper Face Jacks. As we stood in line, one of the bouncers recognized me and nodded, ushering us all forward and giving us VIP access.

I had a girlfriend at the time, so I wasn’t going out to meet anyone, but I was feeling the increased attention. People would come by all night to chat or watch from afar, wondering why others were doing that. Who is your man? I would walk around Dundrum

Mall and notice the heads turning, whispers between friends. It made me uncomfortable. Before I left the house, I started worrying about what I was wearing.

how did i introduce myself I was only 21, an immature college student, and while part of me wanted to go on a night out, be the guy I stroked my ego, a much bigger part just wanted anonymity, normalcy.

The gold medal, as big as it was, also affected my relationships. After Madrid, I started to prioritize athletics more. Before I wanted to give a speech, but now I had to. Training began to absorb so much time and energy that there were many weeks when I didn’t see enough of my girlfriend, which caused conflict. We were from different backgrounds. I was involved in sports, he wasn’t, and it was difficult to understand and empathize with the other person’s point of view.

“Why don’t you go out on Saturday?”

“Because I have 6x300m on Sunday morning.”

The win in Madrid reinforced the need to be professional, to prioritize athletics above all else, even to people close to me. My girlfriend and I broke up later that year, and while post-gold attitude change wasn’t the only reason, it was definitely one of them.

For some people fame is a goal, a dream, but for me the novelty of it wore off quickly. It felt exhausting. One day I was sitting at home hungry and I was thinking of going to the store. But I stopped myself. Why? I was afraid to run into someone who would ask me about athletics. It sounds silly, a real first world problem, but it had become a constant and started to wear on me. I just wanted everything to be normal. But they weren’t.

When I returned to training, there was an influx of new athletes in the group. People said: “This is great, they’re all here because of you.” Meanwhile I thought. “What?

about me I still have a season to go. Why do things change?’ There was a weight that came with being famous that felt like a burden to me. I dreaded the outdoor season. Suddenly there was pressure, anticipation. This was no longer just a hobby.

My neighbor came in one day and although he meant well, he voiced what many were thinking. “We knew you were good, but we didn’t think you were this good.” I had come

nowhere to win a European title and sometimes people assumed I was overwhelmed as a result, that people were knocking on the door to give me cheques. The reality was so different.

I didn’t have a shoe or outfit sponsor and bought the spikes I wore in Madrid myself. The only funding I had was a €4600 grant and there was zero prize money to win

Europeans. I soon realized that money wasn’t going to fall off the tree because the value of athletes is so much less than the value of team sports.

Madrid was something I never expected. But when I got home and things settled down and I had time to think, my old insecurities reared their ugly heads. Impostor syndrome intensified.

Was I just lucky? Did the stars align because everyone ran that day?

That golden moment was magical, as were the celebrations with friends, family, teammates and fans. But when I thought about preparing for the final, the only time I felt relaxed was when I started my warm-up. Every moment before I hated life, I just wanted it to end.

I had to do something about it because I couldn’t face it every championship, having panic attacks and feeling nothing but dread before I fired the gun. You might think that a big win would instill confidence, remove some doubts. But for me it just added to them. I struggled more after Madrid because suddenly people were interested.

“When are you going to race again? Will you go to the Olympics? Will you win gold?”

Before, no one was interested, but now I felt the eyes, the attention.

Nothing has changed in my daily life, but people’s expectations of me have changed. Suddenly a lot of people wanted me to do things for free. It’s not a bad thing to show up at events

medals or say a few words and it’s only right to give something back to the sport. But Mom is a good person, and sometimes she was too good. He used to come home and say: “David, there’s this woman I know who’s a teacher, and they’d like you to come down to the school and give a speech.”

It was hard to say no, especially considering the requests often came from people I knew. But that meant I was being pulled over left, right and centre, and training also became a social engagement where I would be asked to show off the medal.

Two weeks ago no one gave an as**t and I could train in peace.

I would try to oblige people because that’s the kind of person I am, a people pleaser, but elite athletics requires a level of selfishness and it’s hard, very hard to know where

draw the line But if you don’t, you become too busy doing things that don’t necessarily help your career or reward you financially, solely out of fear of saying no.

You’re damned if you do, damned if you don’t.

Going into Madrid I didn’t have the confidence to believe I could win a medal, but when it happened I was blown away. I heard what everyone was saying and I started to absorb it.

You’re going to the world finals. You will receive an Olympic medal.

These things that hadn’t been in my head before moved front and center. When a month or two passed without any sponsorship offers, it was clear that a European title was not enough to earn a good living from the sport. Not even close. I thought of this quote from Nelson Mandela. “After climbing a great hill, one only finds that there are many more hills to climb.” Outdoor trailer season was looming on the horizon and I hadn’t even stopped to enjoy my accomplishment. All I could think about and obsess over was what happened next. S**t, now I have to duplicate this.

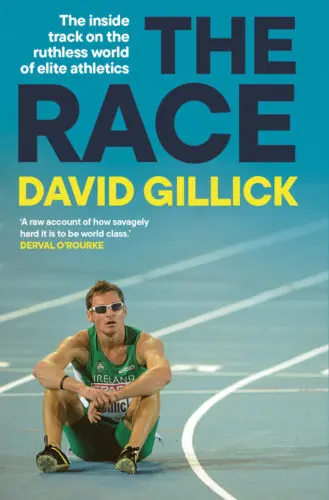

The Race: The Inside Track to the Ruthless World of Elite Athletics, published by Gill Books, is out now.