PEBBLE BEACH, Calif. – Eighteen months ago, on a golden Sunday night at the Presidents Cup in Montreal, Fluff Cowan’s curly mustache.

“Oh, I don’t know,” said the legendary caddy, his New England accent masking the fear he felt behind a tuft of snow-white hair.

He paused, turning the idea over in his head once more. He’s been asked some strange questions in 47 years as one of the most prolific giants in golf history, but none like this one.

How could he capture the entirety of his caddy experience … in a single song?

“Well, I guess the first thing that comes to mind is—in the ways that she sat and flowed—”

He paused once more, painful.

“I think I’d have to go with ‘Trucky,'” he said.

The conversation progressed, but Cowan seemed to stick with that title, content with his selection. It captured his spirit, his history, and critically, his favorite band: the Grateful Dead. A few beats later, his face broke into a smile.

“I was just a driver” stupid.“

Cowan turned 78 on Saturday, two days before the start of the golf tournament that has also come as the start of a new year: the AT&T Pebble Beach Pro-Am. But the start of this senior golf season in Northern California has lost some of its luminescence colored in 2026. In early January, the world learned of the death of one of Cowan’s heroes: Bob Weir, the legendary singer of the Grateful Dead.

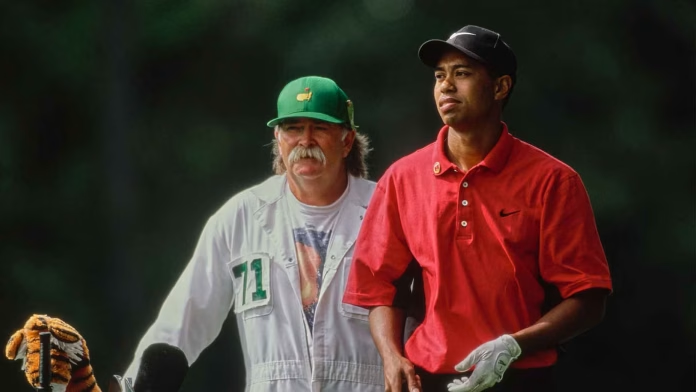

Weir’s death has cast a strange pall over Deadheads like Cowan, who often wore a Jerry Garcia tee in caddy for Tiger Woods. For those whose lives revolved around the rhythms of the Grateful Dead’s concert schedules and (plural) retirement tours, the band was more religion than music. And in the church of the dead, Weir was the heartbeat.

“In my mind, Bobby embodied the whole culture of the Dead, there’s kindness and love,” said Gil Hanse, the golf course architect (and lifelong Deadhead). “Obviously (original Dead drummers Mickey Hart and Bill Kreutzmann) are still here, but it seems like the leader of the band has left the scene.”

Interestingly, Weir’s death has also thrown up a strange concern golf world, where the dead have quietly infiltrated many of the sport’s highest chambers.

“The Dead has probably been the soundtrack to 70 percent of the holes I’ve formed and worked on in my career,” Hanse said. “So yeah, there’s a nice legacy there.”

Perhaps no country speaks to both Dead Heads AND Golf lovers love the Bay Area. Pebble Beach is just an hour down the road from Dana Morgan’s music store in Palo Alto, where Garcia and Weir first met as teenagers, and just two hours from Golden Gate Park, where Weir played his final three shows in the summer of 2025 (coincidentally just a few feet from one of America’s the most popular municipal revitalization projects). Consciously or subconsciously, golf’s visit to the region this week has given the sports legion of Deadheads an opportunity to mourn.

“I felt very upset about it,” Hanse said. “I didn’t expect this. It’s been a lot harder than I thought.”

There is, of course, a profound irony to Weir’s legacy stretching over the Monterey Peninsula’s most manicured cliffs. Golf is a well-hardened sport of fetishized isolation, the kind of place where even appearance countercultural impulses can cost you a seat at some of the sport’s most popular tables; Dead gigs feature the type of individuals who openly question the timing of their last shower. (It should also be noted that if you are going to scientifically engineer the diameter VS. of Shakedown Street—the Dead’s famous pre-concert tailgate, where sun-beaten commuters peddle tie-dyed T-shirts and psychedelic drugs with startling nonchalance—you can end up with a place that looks a lot like 17 miles by car.)

And yet, like a particularly stubborn case of lice, golf can’t save itself from the dead. A thriving underbelly of rejects and hippies flood the box yards and maintenance crews (and, in many cases, the membership lists) of America’s biggest clubs with Dead iconography; while golf’s countercultural (gentle) moment of the 2020s has helped some clubs bring Touch of gray green edge.

“Love them, need “They, they can’t live without them,” Cowan said, capturing the spirit of dedication that heralds construction sites across the country with impressive brevity.

From a distance, the correlation may sound trivial, but spend time around golf’s true Deadhead contingent and you’ll realize that the sport and the group share a heartbeat. For all the occasional suffocation of golf, the sport’s best traits can literally be lifted from the central themes of a Dead concert: sensitivity, serenity, creativity, craftsmanship. And, hell, is there a better place discover the wonders of nature than on a particularly psychedelic golf course?

“Everybody in our band, The Cavemen, we all have a role to play – and there’s a kind of foundation – but then outside of that foundation, we can take it in any other direction we want,” says Hanse. “I think that’s kind of the moral of the dead. Every night was different in how the music was performed and presented. We want the creativity to come out in the improvisation.”

The mainstream audience helps too. Many of the original Deadheads have now aged into boomerdom, where golf is a national pastime, while many of the daredevils responsible for keeping the sport afloat—those crazy enough to pursue a career in golf – have done so precisely for the chance to break the shackles of a desk job and a nine-to-five job. For this band, Dead is a siren song.

“I’ve often said what we offer people is music with a little adventure in it,” Weir said in 2016. “People who like our music, come to our music, are drawn to our music — they’re people who are looking for a little adventure in their lives.”

Ultimately, that same spirit of adventure carried Weir to the end. He played his final shows with the Dead in Golden Gate Park in August — part of a 60th anniversary celebration of the band that drew more than 150,000 people to San Francisco. Hanse was among the crowds for all three nights, having gotten “on the bus again” with his wife, Tracey, in the last years of Weir’s life. No one knew it then, but Weir was waving.

“The first show was pretty rough, Bobby obviously wasn’t well,” Hanse said, briefly slipping into the Deadhead vernacular. “But then Saturday and Sunday night was just… magic.”

If an anti-establishment bent brought the Dead to golf, memories like these are what have kept them going. Beneath the logos, the hippies and the music is a spirit of something much greater: goodness.

“From the outside, people can draw whatever conclusions they want about golf, but true Golfers find that same peace and quiet when they’re out on the golf course,” Hanse said. “I mean, you’ve had three nights where you’ve had 50,000 people — and there’s been no crime, no violence, nothing. Maybe some people were… chemically altered in the way they felt, but they were there to celebrate something that was pure. And I think we celebrate the game of golf and the landscapes we play it in for very similar reasons.”

For many Deadheads, this idea was the hardest part of Weir’s death. If the leader of the group was no more, what would prevent the spirit of the Dead from crossing over with him?

Fortunately, there have already been signs to the contrary. One arrived on the morning of January 10, the same day news of Weir’s death reached Hanse on a golf course in New Zealand.

As Hanse found himself dealing with an unexpected wave of grief, he received an unexpected visitor: his five-year-old granddaughter, Peyton.

Peyton heard that her grandfather was upset and she took matters into her own hands. She approached Hanse giving her a gift.

“She went out and got me some flowers from the little meadow in the backyard,” Hanse said. “And she said, ‘I know you’re sad, so I want to get you some flowers for your friend.'”

Hanse cried over the gift. He cried again sharing the story.

They were tears of joy. The kind that comes after an unusual act of kindness. His old friend Bobby would have loved that. He would have loved it.

But he would have liked MOST what came next, when Gil Hanse started his tractor and kept trucking.

You can contact the author at james.colgan@golf.com.